by Peter Godfrey-Smith

The author is an Australian philosopher and professor specialising in the history and philosophy of science. Also known by the less inspiring title of Other MInds: The Octopus and the Evolution of Intelligence, this book became a best-seller when it came out in 2016.

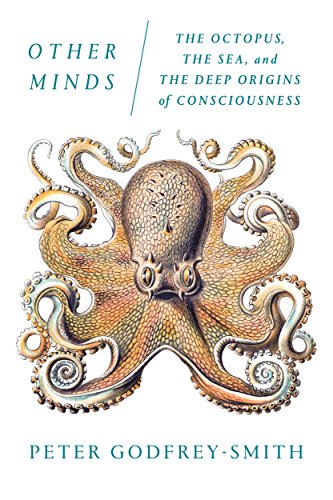

The framework of the book is straightforward nature writing, as Professor Godfrey-Smith records individual octopodes and cuttlefish he has met off the coast of Australia, and his observations on their personal and social behaviours. Photographs and drawings describe, for example, the unfortunate male octopus who was trying to impress a rival with his size and ferocity when a fish crept up behind him and bit him on his pointy end, resulting in an undignified jump; and the endlessly inventive and expressive colour displays of the giant cuttlefish. This is fascinating in itself, as Godfrey-Smith and his colleagues discover a hitherto unknown octopus society, where these generally solitary animals congregate at an ideal nesting site, building their dens under piles of discarded shells and learning how to interact with each other at close range.

Around this framework, however, Godfrey-Smith has woven much deeper speculations about the nature of life and mind. We learn about the probable evolutionary path of molluscs in general and cephalopods in particular, pieced together from the remains of animals many of which had few hard parts and do not fossilise well. We learn about possible explanations of ageing and why some species age much faster than others.

Above all, the author speculates about the nature and evolution of intelligence and of consciousness itself – of the point at which, as Professor Godfrey-Smith says, it first began to feel like something to be an animal, and how that state may have come about. We learn how consciousness can become divided into disconnected areas, by human intervention in frogs and by accident in humans, and what that tells us about cephalopods whose limbs have their own individual brain-ettes, partially independent of the central mind.

My only quibble – and it affects only one or two paragraphs in the whole book – is that the professor takes it for granted, as something absolutely proven, that there is no such thing as a soul and that consciousness is purely mechanical, when that isn’t really something we can know because we don’t currently have a way to test it.