Please note, before we begin, that when I say “Creationist” I’m not referring to those theists who accept the reality of evolution, but regard evolution as part of God’s Plan in a created universe which was at least partly pre-planned, and might have been given the occasional divine nudge: this is a perfectly respectable idea, although currently untestable. Creationists, self-identified as such, are those who believe that the Creation stories in Genesis are literal descriptions of the dawn of life, not just a fancy metaphor for it, and that complex life-forms were poofed into being ready-made by God. They somehow manage to insist that Genesis is literally correct in every line, even though it contains two slightly different and not entirely compatible versions of creation.

The most obsessive kind, called Young Earth Creationists, also believe Bishop Ussher’s 17thC calculations of the minimum elapsed time since the Biblical creation of Adam and Eve, and that the world is only about six thousand years old. Some do accept that organisms evolve in relatively small ways which they call “microevolution”, but deny the possibility that many microevolutions eventually stack into a macroevolution, a major change of form: although they can never provide any reason why this should be so.

Creationists are almost by definition fundamentalists, so they are deeply indoctrinated with the idea that knowledge is something which is handed down to you by Authority. Many of them not only don’t understand the evidence for evolution, but in a very real sense, they don’t understand what “evidence” means. To them, it means what an Authority figure told you, not something gained by studying external reality and analysing what it does. An Authority figure, either their parents or their pastor, told them the Bible was the inerrant word of God, so then the Bible is seen as itself coming from Authority – an Authority which they have been told by Authority never used metaphor or simile or fictional parables (they know that Jesus used parables and metaphors, and they believe that Jesus was an aspect of God the Father, but are absolutely certain that God the Father never used parables or metaphors – except when it comes to the Song of Solomon, which they believe isn’t really about sex).

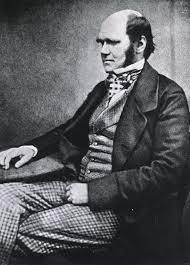

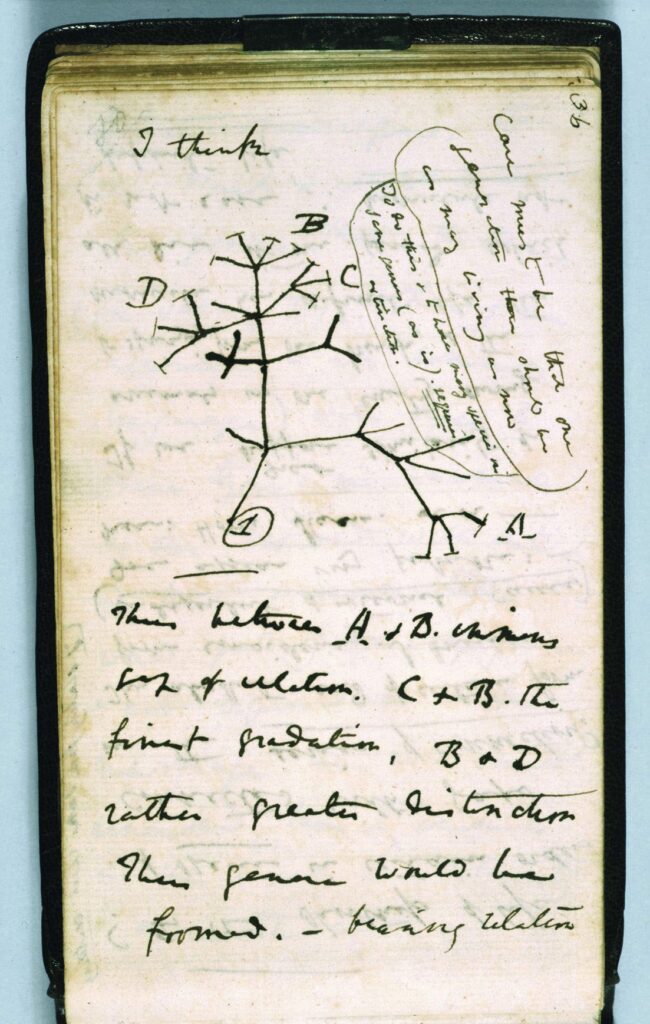

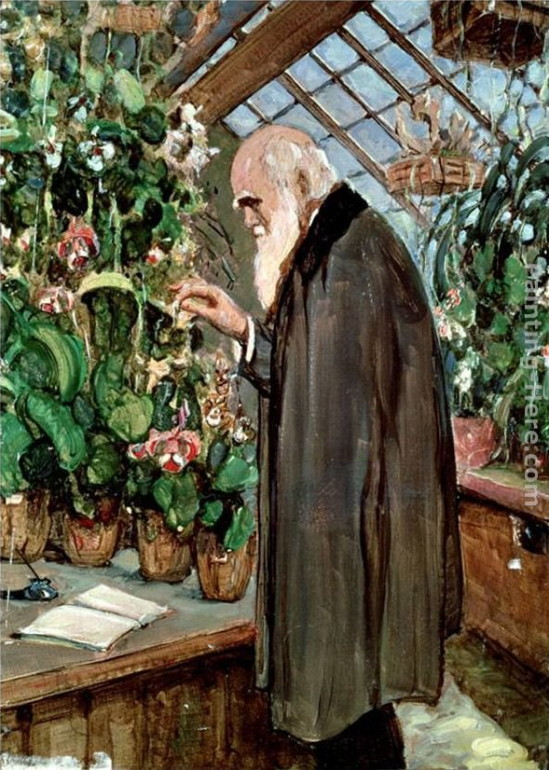

For this reason, many, perhaps most of them have no understanding of what science is or what a scientist does, and are convinced that so-called “evolutionists” regard Charles Darwin as an Authority. They imagine that if they could discredit Darwin personally then people will stop believing in his ideas, which will have been shown to be untrue because they came from a flawed source – in the same way that Scientology is cast into doubt by the fact that L. Ron Hubbard was a massive charlatan who made shit up. This is why they habitually refer to the acceptance of the science of evolution as “Darwinism” – when they aren’t calling it “evolutionism”. In both cases, the aim is to make it sound like a Cult of Personality rather than a body of objective observation of the world.

Of course, The fact that Isaac Newton was a deeply horrible person with some deeply weird ideas never stopped anyone from believing in gravity, or caused anybody to float into the sky. Some Creationists then take that as proof that Newton was an Authority, and therefore that the fact that Newton believed in a literal interpretation of Genesis gives added authority to Creationism, even though Newton was not a biologist and never studied the alternatives. To them, what Authority says must be true and they don’t get the idea that academic authorities are only authorities on subjects on which they are expert, and that the opinion of a top-level physicist on evolution is only marginally more significant than the opinion of a random burger-flipper.

They also don’t get that scientists study objective truth (or at least try to), and if one person doesn’t make a given discovery, sooner or later someone else will: nor that science by its very nature moves on, adjusts its course in the light of new evidence, and leaves its earlier heroes behind. Scientists are not gurus, discovering some revelation which is specific to them, and which stands and falls by their word, like religious revelations. Scientists are just people who observe the world, describe it, and have ideas about how the world works which they then test. If their ideas pass those tests, other scientists pick up the ideas and do further work on them. Each individual scientist is just a replaceable cog in a big machine of advancing human knowledge, and their personalities are irrelevant, unless those personalities include fraud or intellectual sloppiness. Even if they do, the process is self-correcting – a fraud or error will eventually be uncovered when other people try to replicate a result, and can’t

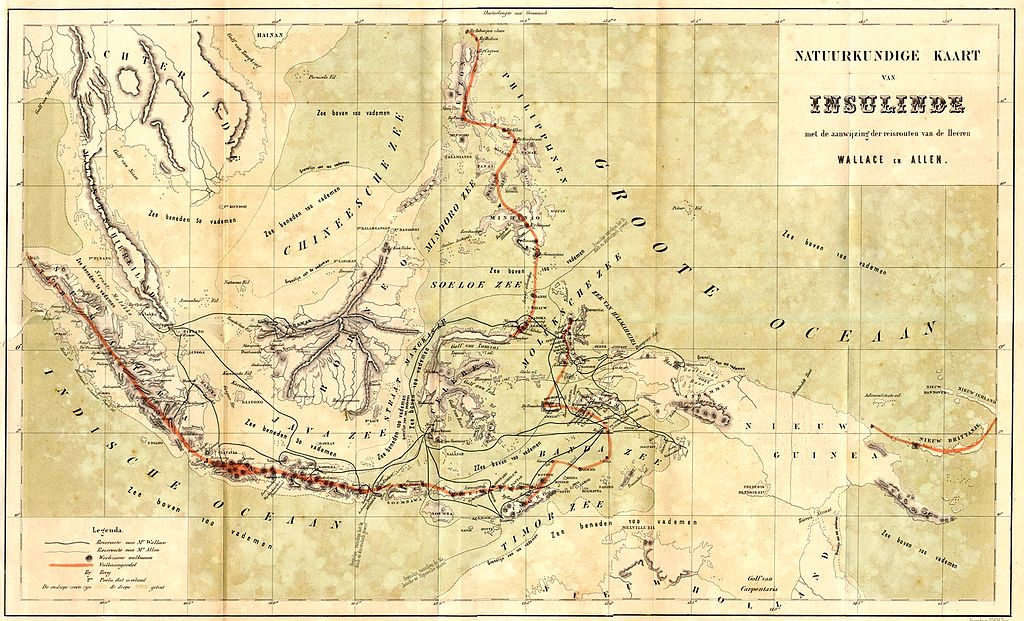

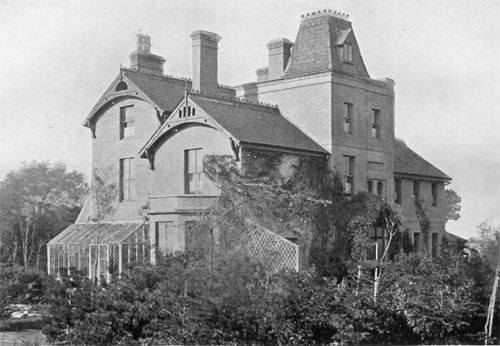

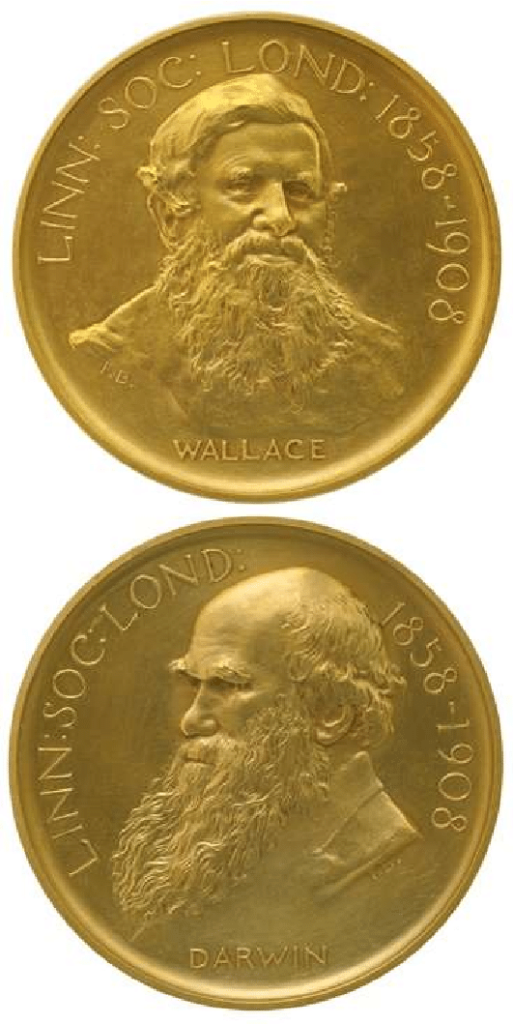

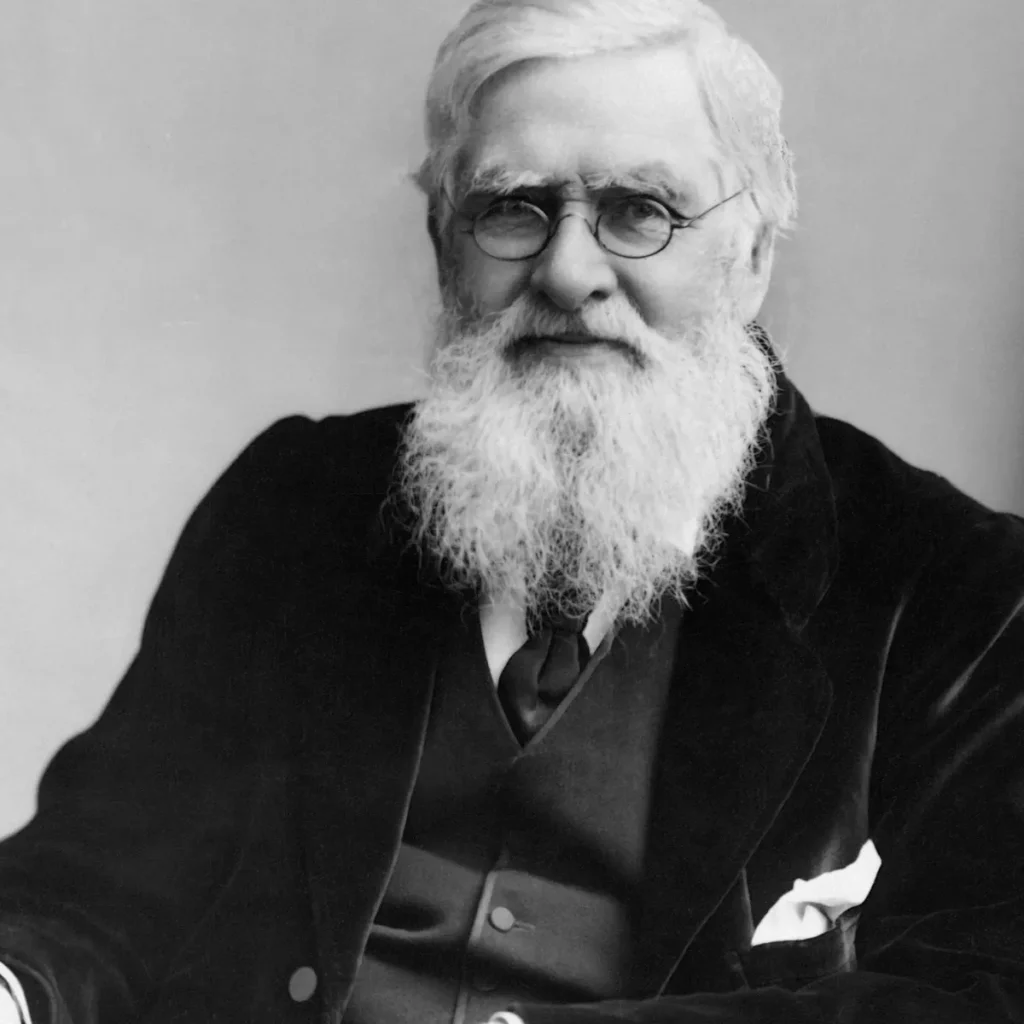

Darwin was a great researcher and science-writer, but he is no more relevant to the modern study of evolution than Galen is relevant to modern medicine. He wasn’t some kind of prophet – he was just a guy who observed the world and then wrote about it, using his necessarily imperfect Victorian knowledge, and if he hadn’t introduced the world to natural selection, someone else (probably Alfred Russel Wallace) would have done so within a few years. In fact, other people already had, although Darwin wrote the first full-length published book on the subject.

Darwin wasn’t the first person to discover evolution, or even evolution by natural selection. He wasn’t even the first 19thC British man to do so, but the second or third (more on this later). Yet, Creationists – or “Cretinists”, as I’ve taken to calling the most dishonest of them – constantly harp on what Darwin did or didn’t say, in the hope that discrediting him will discredit evolution. They claim – entirely falsely – that Darwin recanted of evolution on his death bed, as if the idea stood or fell with his opinion of it, and as if tens of thousands of later researchers hadn’t confirmed it. They also repeatedly try to make out that Darwin was a racist because his most famous work was called On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.

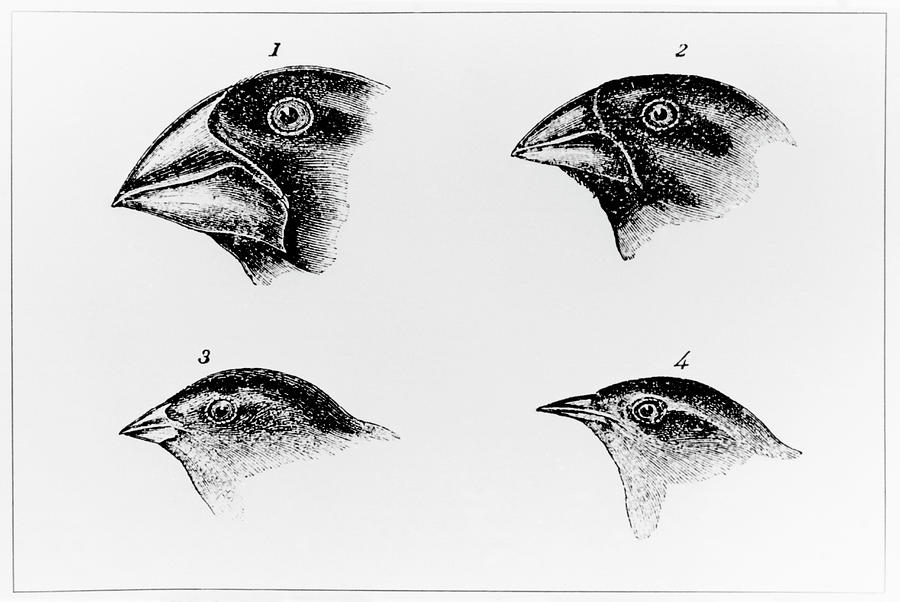

Of course, the idea that “race” means “a group of humans with a particular skin-tone” is fairly modern and largely American. It really just means “a group with something in common, probably connected by blood”, which is why we see statements like “The Macdonalds are a proud race”. Darwin was using it to mean what we would call a family line with shared genes – mainly family lines of cabbages and fluttery little birds – but he didn’t know about genes, so his terminology was woolly. Most of the Creationists who claim he was a racist probably know they are making shit up.

Insofar as Darwin had opinions about human “races”, he was a Victorian Englishman who thought that an English education was the measure of a man, and that what he saw as primitive cultures would be overwhelmed by what was then the modern world; but he also thought that the black slaves he encountered on his travels were clearly a superior type, both physically and in character, to their Portuguese masters. But even if he had been a racist, that would make no difference to the accuracy and authority of his scientific discoveries, any more than Newton’s difficult personality invalidates gravity. Both have been validated by many hundreds of thousands of other scientists since, using instruments Darwin and Newton could only dream of.

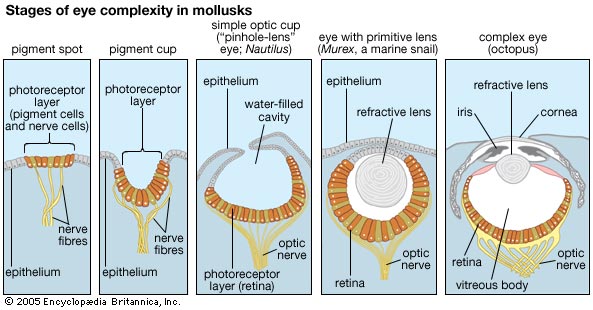

Creationists and proponents of Intelligent Design (a.k.a. Creationism-Lite) like to harp on the idea of “irreducible complexity”: the idea that there are some organs which are so complicated and specialised that they couldn’t have evolved, because the intermediate stages of development would not have been useful and selected-for. In chapter #6 of On the Origin of Species, Darwin addressed this problem, which he termed “Organs of Extreme Perfection”. Creationists love to quote his opening line, which starts: “To suppose that the eye with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest degree.”

Again, however, they are taking this statement completely out of context – innocently in the case of those who have never read the whole passage, and with deliberate dishonesty in the case of those who have. The full passage runs:

To suppose that the eye with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest degree. When it was first said that the sun stood still and the world turned round, the common sense of mankind declared the doctrine false; but the old saying of Vox populi, vox Dei, as every philosopher knows, cannot be trusted in science. Reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a simple and imperfect eye to one complex and perfect can be shown to exist, each grade being useful to its possessor, as is certainly the case; if further, the eye ever varies and the variations be inherited, as is likewise certainly the case; and if such variations should be useful to any animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, should not be considered as subversive of the theory. How a nerve comes to be sensitive to light, hardly concerns us more than how life itself originated; but I may remark that, as some of the lowest organisms, in which nerves cannot be detected, are capable of perceiving light, it does not seem impossible that certain sensitive elements in their sarcode should become aggregated and developed into nerves, endowed with this special sensibility.

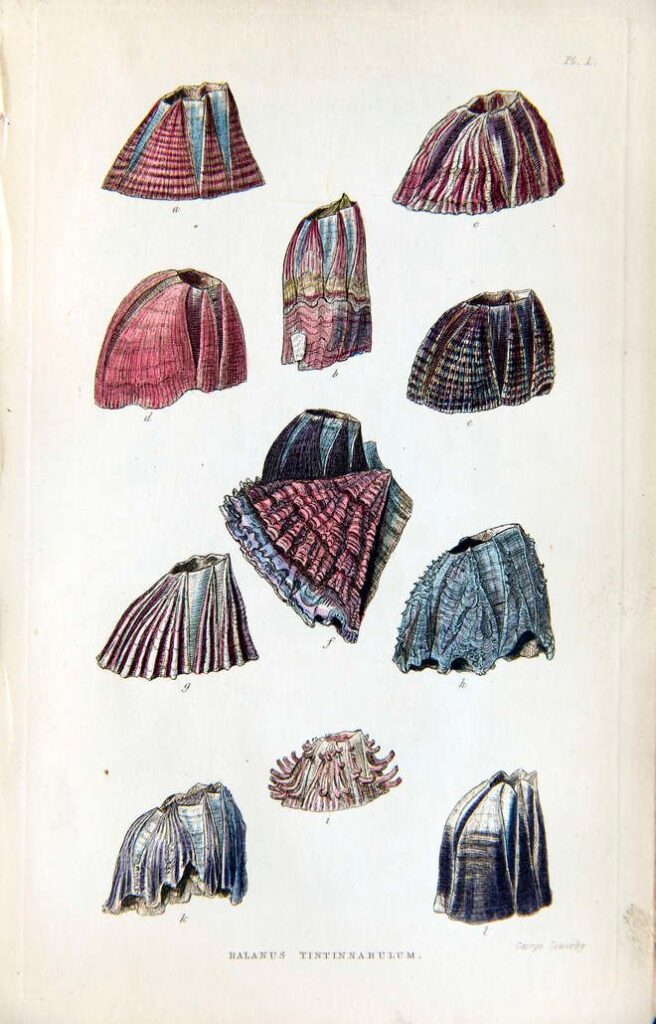

Note that: “if numerous gradations from a simple and imperfect eye to one complex and perfect can be shown to exist . . . as is certainly the case“. Darwin, that expert on barnacles, corals and earthworms, knew that various types of simple-to-complex eyes can be found in extant species of invertebrates.

And Darwin, as I said, was not the first to discover evolution. He was just the first to pull all the different elements of it (as far as those were known in his day) together, and then write a good, clear, readable book on the subject, with detailed examples. But the basic idea of the slow transformation of species over long periods of time had been known about, in one form or another, for well over two thousand years. When I got the idea for this essay, I expected to find maybe eight or ten thinkers before Darwin who had had strong ideas about evolution: but in fact there were nearly sixty, and those are just the ones I know about.

Evolutionary thought and palaeontological knowledge before the Common Era

So far as we know, Homo sapiens has been around for 310,000 years, and Neanderthals and Denisovans went back about 430,000 years. We, their descendants, have had writing for less than 6,000 years, and initially writing would generally have been confined to an educated elite, so those early peoples didn’t have a wealth of research behind them that they could read about in books or on websites. But they had language and memory and orally-transmitted poetry and stories about what their grandmother told them, and they were no less intelligent than us. Indeed, those who lived in areas where there was enough food for a growing child, especially those who lived on the sea-shore or near a salmon-run, may actually have been more intelligent than us, due to a diet high in oily fish and low in pollutants – at least until they got sophisticated enough to use lead pipes and lead-glazed pottery.

So, sneering at the authors of the Bible stories as illiterate ignoramuses is itself ignorant. They were fully intelligent, observant people, even though they didn’t have centuries of written textbooks to fall back on, and the structure of the Genesis stories suggests that their authors had already observed that fossils came in stratified layers, that different sorts of organism were prominent in different layers, and that human remains were only found in the topmost levels. This is despite being handicapped by the fact that the Mediterranean area’s violent geological past means that most of the fossils found in the area come from the Age of Mammals, with little to see from before the start of the Miocene about 25 million years ago.

They don’t seem to have seen enough detail to know that forms slowly morph into other forms – not surprising with such a limited snapshot of the recent past to work from – and neither at first did other ancient peoples. There’s a fascinating book called The First Fossil Hunters, by Adrienne Mayor, which looks at early interest in and attitudes to fossil finds. Even in the Stone Age, interesting portable fossils were widely collected and (to judge by the distance some had travelled) traded, and used to make attractive beads for jewellery. There were even Stone Age European hunters who interacted with real live cave bears, but still made their jewellery from the fossilised teeth of their fore-bears.

The book mainly concentrates on how the Ancient Greeks, Romans and Egyptians collected, observed and interpreted fossils, although Mayor mentions in passing Hebrew folk traditions of the period, based on fossil finds. The 1stC Jewish historian Josephus spoke of legends of terrible, non-human giants wiped out by the Israelites, and Mayor states that “In the Greco-Roman mythic tradition, and in ancient Hebrew traditions as well, all species were not created in one fell swoop, and novel life-forms appeared and then disappeared over time”. This last seems to be based on some scholars’ interpretation of the Old Testament [ref: Charles DeLoach 1995, Giants: A Reference Guide from History, the Bible, and Recorded Legend, p.106-8], and raises the possibility that Creationism is very much a modern phenomenon..

The Greeks never pretended that fossils were anything other than once-living organisms turned to stone, nor could they reasonably do so, since the island of Lesbos has an extensive fossil forest with many tree-trunks still standing and still being very obviously trees. By the 4thC BCE they had a basic understanding of the process of petrification, which can happen very rapidly at certain hot springs and other mineral-rich waters (the famous Petrifying Well near Knaresborough in England can turn small objects to stone in just a few months, and the local gifte shoppe sells little fossilised teddy bears). Theophrastus, 372—287 BCE, a pioneering geologist who was born on Lesbos in the midst of the stone forest, and later succeeded Aristotle as head of the Lyceum, wrote a treatise On Stones which discussed how certain minerals could change objects to stone. Unfortunately his two-volume work On Petrifications has been lost.

Animal fossils in the Mediterranean area come mainly from comparatively recent extinct mammals, many of them very large, but they look ancient because the turbulent geological history of the area has left these bones pockmarked and broken. On the other hand, travellers from Europe had some access to – or at least to reports of – dinosaur remains in India and Mongolia which were far more ancient, but appeared more recent due to their better state of preservation.

The Greeks, and later the Romans, made a stab at reconstructing the animals these stone bones came from. In the case of their local, damaged mammalian fossil finds they realised these were forms which were no longer around. But the bones were often disarticulated and found in jumbled groups without their skulls, and one mammal femur or scapula looks much like another, so they generally assumed they came from giant humans or cattle which were similar to smaller modern counterparts and fairly recently deceased – hundreds or at most thousands of years dead, rather than millions – although some scholars did get the idea that some of the bones predated humans arriving in the area, and came from a time they envisaged as close to the dawn of life. Actual palaeontology influenced myth to the point that they accepted that the “giants” in their mythology might be bizarre quadrupeds rather than humans, but if the arrangement of the bones wasn’t obvious they had a preference for putting them together into an approximation of humanish giants.

From this, we get the Cyclops, almost certainly based on the skulls of mammoths or of the Sicilian dwarf elephant, Palaeoloxodon antiquus falconeri, with the trunk’s socket reinterpreted as a central eye. Such skulls were at least sometimes correctly identified as those of elephants, probably if they were found with full-sized tusks still articulated; but then they were assumed to have been the war-elephants of ancient kings. A kind of feedback loop developed, where fossil bones were assumed to be the remains of heroes of the past, whom mythology said had been giants, so the discovery of fossils reinforced their beliefs in their mythology – but that mythology had probably been inspired by ancient fossil finds to begin with. To make things even more confused, sometimes very early Greek farmers would dig up giant fossils, assume they belonged to some great hero and rebury them with a proper coffin and/or grave goods. Centuries later, after the first find had been forgotten, new excavations would uncover the previous ceremonial reburial, and take the presence of a coffin and grave goods as proof that the bones were human, and important. Then these supposed hero’s bones would end up as sacred relics in some temple, like saints’ bones and presumed fragments of the True Cross in Catholic churches two thousand years later.

The origin of the Greek version of the griffin is slightly different. Mayor argues, convincingly, that griffins, with their eagle beaks and lion bodies and knobbly heads, were inspired by travellers’ tales of Protoceratops and Psittacosaurus skeletons, which are extremely common in the Gobi desert, and lie around looking as if the animal that owned them died about 20 years ago, instead of 70 million. They may even have found some fossils that had the imprint of feathers. In this case, because of the apparent freshness of the remains, the Scythian tribesmen who saw the skeletons firsthand assumed the species of animal that owned them was still around. The stories reached Greece as referring to a “four-legged bird” (not a bad description of a quadrupedal dinosaur) that still survived in what Terry Pratchett called “forn parts” and was a normal, mortal animal with normal animal behaviours, not some holy relic of an age of giants – even though, perversely, that was just what they were. Something similar happened with fossil-inspired rumours of dragons surviving in the mountains north of India.

The wings which are commonly credited to griffins, at least to female ones, are harder to explain than the four-legs-and-a-beak, but may be due to garbled descriptions of the Ceratopsians’ neck frills. That would explain why many Greek and Etruscan illustrations of griffins, especially earlier ones, show the wings as stiff blades which look like decoration rather than useable limbs, with a tightly-curled top which follows the same curvature as a side-view drawing of a male Protoceratops frill. It’s easy to see that the artist may have become confused as to where exactly the animal’s neck was, especially if some of the skeletons were broken, and has attached that stiff curve to the shoulders instead of the back of the head, and interpreted the prongs which stick sideways from Protoceratops cheeks as being stiff ears.

The Regolini-Galasssi tomb, the burial site of a wealthy Etruscan family living (and dying) in Caere in Italy in around 650—500BCE, contains many griffin-based decorations. There’s a website which is dedicated to virtual reconstruction of the tomb, and which has an article Did griffins really exist? which examines the fossil origin of griffins at length.

So, interest in fossils is old and widespread. We know that prehistoric Europeans made pendants out of fossil ammonites, In Malta, as far back as the Stone Age, fossil shark teeth were used as tools to scrape distinctive patterns into pottery, while ancient elephant tusks and helical fossil snailshells were collected in the temples, along with large models of the same shells made from limestone or ceramic – although we don’t know whether these were honest sculptures or bogus our-fossil-shells-are-bigger-than-your-fossil-shells fakes. In Crete of the same period imitations of fossil shark vertebrae were shaped from gold and marble. In Egypt, as in Greece, local people collected small fossil curios to give as offerings at temples. Devotees of Set, god of darkness, collected river-polished black fossil bones, some human, some not, and piled them up at the shrines of the god, some of them wrapped in linen and ceremonially reburied, while other fossil bones were assumed to be relics of the murdered and resurrected Osiris. Pre-Colombian Native Americans also collected stones with good fossils in them, and saw large fossil skeletons as the remains of Thunderbeasts (not forgetting that “Brontosaurus” means “thunder lizard”), killed by some terrible ancient storm. Mayor has found evidence of almost industrial-scale fossil-collecting in the Classical and Ancient Egyptian world, with shiploads of fossil bones being transported, and many of the most interesting and spectacular finds ending up on display in temples, or in a wealthy man’s collection of heroic curios.

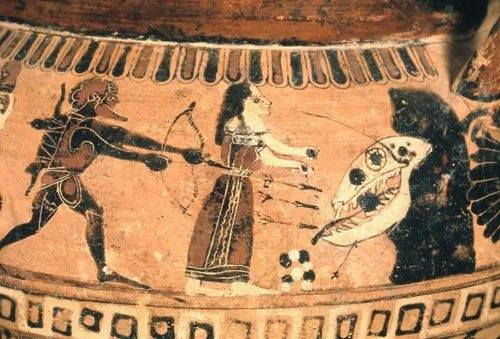

A few of these specimens or their depictions still survive. One of the most striking is the Monster of Troy vase, which shows humans firing arrows and throwing stones at a monstrous head emerging from a rock. This is the ultimate in shrink-wrapping, since it portrays a fossil skull as if it were the animal itself: Mayor suggests that this was a joke by the artist, to highlight the fact that stories of mythical monsters were often based on bones found in local rocks.

There has been considerable debate about what animal the skull came from. Mayor thinks it is a deliberate composite loosely based on a prehistoric giraffe skull: but personally I’m 90% sure it’s based on a large Ichthyosaur skull which had lost half its beak, and possibly also the back end of the skull. The prominent, segmented scleral ring is typical of Ichthyosaurs, and while most large fossil remains in the Mediterranean area are from extinct mammals, Ichthyosaur remains have been found in Sicily.

Given how large their eye-sockets were it seems to be common for Ichthyosaur skulls to fracture and lose pieces off the back, so I reckon somebody guessed at the angle of the jaw and back of the skull, based on a horse or cow skull. That would explain the dark suture line drawn on the skull behind the eyes, which would mark the edge of the actual fossil. It’s true Ichthyosaur teeth don’t normally slant forwards like that, but the shape is more like Ichthyosaur teeth than anything else, and they sometimes come loose after death and end up at odd angles.

Again, however, the skull was seen as that of some fairly recently dead monster, something fought and speared by human heroes. It was the norm to associate fossil finds with ancient quasi-religious myths. Most of the most famous Greek philosophers, the ones whose ideas echoed through history, saw these stories as tales for children and uneducated peasants, and ignored reports of giants’ bones as beneath their notice; mentioning them, if they did at all, only to dismiss them. For this reason, the history of early palaeontology was overlooked for two thousand years.

The Greek myths, however, did contain the essential idea “There used to be giant creatures which are now extinct” and some idea of species being mutable, although they generally saw this as drastic mutation and reassortment (a two-headed dog mates with a chimaera who then gives birth to a lion and a sphinx) rather than slow evolution. When it came to slow change, many thought that all life was slowly dwindling and diminishing compared to the giants of the past: but some writers, perceptively, saw the stories of wars between armies of gods and giants as a metaphor for past geological change. Inspired by fossil seashells found on land which was now dry, some Classical myths spoke of between one and five great floods each of which destroyed all life (except, according to the most popular version, the Titans Deucalion and Pyrrha), after which new species had to be formed. According to Ovid (43BCE—17/18CE), some of the new forms were said to be reiterations of what went before, while others were wholly new. As with the Genesis story, there may be observation here of the fact that fossils came in layers; although this is much less obvious around the Mediterranean than in many other areas. The Greeks certainly had a much better idea of the age and mutability of the world than modern Creationists do.

From the 6thC BCE, Classical philosophers sought for purely natural, physical causes for the form of the Earth, and speculated about the origins of life. The philosopher Xenophanes (560—478BCE) observed marine fossils of fish, invertebrates and seaweeds and proposed that life had proceeded by a series of floods and renewals, similar to the Deucalian Flood myths but without involving any Titans, and this idea became accepted as mainstream. However, these marine fossils were very similar to modern life, and so there was no need to see life itself as mutable. “Giants’ bones” didn’t fit comfortably into the new, naturalistic explanations the philosophers were building for the world. We can’t be certain, because so many ancient writings have been lost, but it certainly looks as though with the possible exception of Theophrastus (371—c. 287BCE) and his lost work On Petrifications, they ignored them as being impossibly tainted by religion, and therefore either untrue (despite being on public display in the temples) or negligible. In Plato‘s dialogue Phaedrus, he has Socrates say that philosophers reject or rationalise popular myths, and that when it comes to mythical monsters “. . . I don’t concern myself with them. I have no time for such things. I accept what is generally believed, and pursue more serious matters”.

It’s ironic that the Greek philosophers seem to have ignored the fossil evidence because they saw it as too connected with religion, while modern Creationists ignore it as not being connected with religion enough. And like Creationist theologians, the Greek philosophers were concerned with the ideas inside their heads and how much they could impress their peers with those ideas, rather than with producing actual empirical evidence. In addition it’s been suggested that the philosophers, whose whole schtick was trying to fit the world into an organised scheme that made sense to them, didn’t know what to make of the jumble of disconnected and often shattered bones, and so ignored them because they didn’t fit into their tidy worldview – again, rather like modern Creationists.

Nevertheless, the philosophers were edging towards the idea of evolution. The Graeco-Turkish philosopher and cosmologist Anaximander of Miletus, who lived from 610BCE to around 545BCE, began to see life as arising in the sea through the action of the sun on the primal ooze via some kind of evaporation (not a million miles from modern ideas of abiogenesis) and unfurling through some kind of progressive adaptation to the environment. He even reasoned that humans must have evolved from other animals, and ultimately from fish, and could not simply have popped into being, because human babies are so vulnerable and would have had to have had slightly less human parents to care for them.

He wasn’t an entirely enlightened thinker, though: he believed the Earth was a stubby cylinder and we lived on its flat end, and his spin on humans evolving from fish was rather odd – at least as it has come down to us, for nearly all of his original writings have been lost, and we know about his theories only from other people’s memories of them. Based on observations of early human embryos, he seems to have envisaged a race of thorny-skinned fish-people at least some of whose young had human babies growing inside them. At puberty they beached themselves, and then the fish part split and a fully-formed human emerged. It sounds to me as though he had probably observed the caterpillar-chrysalis-butterfly transition, as well. Like the Genesis stories, this is a nice metaphor for evolution as we now understand it, but not to be taken too literally.

Empedocles of Acragas in Sicily, who lived from 495BCE to 435BCE, traveled widely and is rumoured to have died by casting himself into the crater of Mount Etna, believed that there were four elements, earth, air, fire and water, and two forces, attraction and repulsion, and that these had acted on each other to produce random assortments of organs and body parts, weird, hybrid monsters, which were gradually pulled into their modern shapes, or died out when their forms proved too inefficient. So he had the general idea of forms becoming better-adapted over time, but came at it from an eccentric angle. He saw birth and death as merely the assembling and disassembling of these component parts. Sadly, one of the works of Theophrastus which have been lost was a study on Empedocles and his ideas.

It’s worth noting than as a Sicilian Empedocles probably spent a lot of time on the coast, and the Mediterranean has European sea squirts, Ascidiella aspersa, which definitely do look like disembodied bits of intestine looking for an abdomen to join.

Meanwhile, the philosopher Plato (c. 428—348BCE) was the most important proponent of the opposite view. He had some awareness of Deep Time, stating that mankind had “existed for an incalculably long time from its origin”, but he believed that all species were imperfect manifestations of a fixed, ideal template for that species. This viewpoint allowed for so-called microevolution, as species became more and more like their ideal form, and indeed Plato said that “various changes in climate have probably stimulated a vast number of natural changes in living beings”. However, it precluded radical change from one species to another.

Plato’s student Aristotle (384—322BCE) was the first naturalist we know of who attempted to organise extant living things on a scala naturae, a ladder of relationships, although he saw it as fixed. This arrangement to some extent reflected the real course of evolution, with the bottom occupied by simple forms, but perverted it by placing simple forms only at the bottom and dividing organisms into “higher” and “lower” types. But so far as we can tell from his surviving writings, he ignored anything that didn’t fit onto his ladder, including fossils

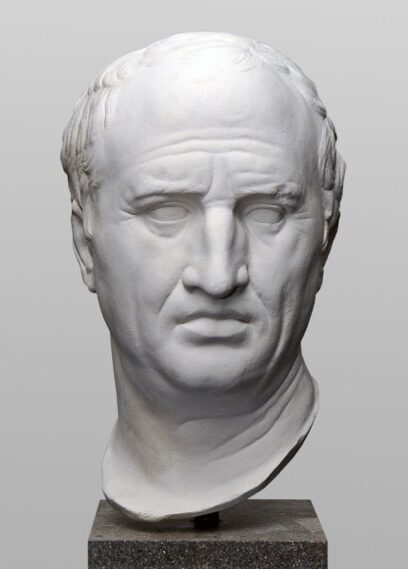

Aristotle saw that an organism’s form fitted its function (although it may make equal sense to say its function fits its form), and the idea that all natural life is, as Cicero (106—43BCE) put it, “directed and concentrated. . .to secure for the world. . .the structure best fitted for survival” became a part of Stoic philosophy. Cicero reported that it was accepted as read by the Hellenistic elite that nature produced forms “best fitted for survival”. In theory this should not completely preclude mutability, but Aristotle and his heirs saw the selection of “best fitted” forms as a deliberate and goal-oriented process and rejected Empedocles’ idea of constant reassortment and extinction. Essentially they had cast out the gods of mythology, and replaced them with a kind of abstract but conscious god of nature. These ideas influenced the later Christian belief in fixed, unchanging species directly designed by God.

A disciple known only as Pseudo-Aristotle (any of several unknown “school of Aristotle” disciples) wrote a text entitled On Marvellous Things Heard, which lists various geological and palaeontological items (burning lignite fields, amber, fossil footprints, petrified human bones etc), as if cataloguing them for a future investigation, but so far as we know it never came. Aristotle’s friend Palaephatus (a nickname which means “ancient tales”), working probably some time in the late 4thC BCE, wrote a work called On Unbelievable Tales in which he tried to explain ancient myths rationally. He explained the myth of the dragon slain by Cadmus whose teeth sprouted armies as elephant tusks belonging to a king named Draco, who was killed by Cadmus, but the teeth were used as currency by Draco’s allies to raise an army. In this, Palaephatus showed insight that the bones and teeth which featured in legend might have come from real animals, but he was adamant that it was impossible for any past species to have become extinct.

Aristotle was possibly the first, or at least the first we know about, to attempt an organised classification of the natural world and a framework against which anomalous fossils could in theory have been compared to identify the ways in which they differed from extant life. But his idea that species were ideal and immutable as they were, and his rigid, formal classification of current species, dissuaded his followers from investigating the giant relics of the past, because they did not fit his scheme, his “ladder”, while living specimens which didn’t fit his pattern were dismissed as mutant anomalies. Again, although he was trying to be rational, Aristotle’s ideas were the reverse of scientific, and more like a Creationist cult, in that his followers decided what results they wanted and then ignored anything that didn’t fit.

In an article entitled The Greek Vision of Prehistory, published in Antiquity 38: 171—78, ED Phillips suggests that the failure of the Greek philosophers to get to grips with the fossil record and attempt to incorporate these extinct animals into their visions of the natural world, or to understand the extent to which species changed over time, was at least partly due to the limited period covered by most Mediterranean fossils, and the way in which geological forces had jumbled them out of order, then spat them out again randomly in landslips and earthquakes. They didn’t really get the chance to look at the stratified layers of different fossil life that we can see in many other regions of Earth. It’s remarkable that the Greek scholars and the authors of Genesis got as far as they did with the limited evidence available to them.

Along with their general belief in the fixity of species, Greek astronomy similarly taught that the stars were unchanging, which discouraged them from recording phenomena such as novae; while Chinese philosophers who believed that nature was mutable made more accurate observations of celestial anomalies. Simultaneously with these Ancient Greek philosophers, Chinese Taoist philosophers such as Zhuang Zhou (c. 369—286BCE) believed that all of nature and the cosmos was in a state of constant transformation, the Tao, and speculated that species changed their form in response to their environment. China was another region where fossil collection was a big deal; possibly starting as far back as 1,000BC, since the I Ching refers to “dragons encountered in the fields”. Fossil bones – collectively called “dragon bones”, although people knew they came from many different species – were later seen as a winter cash-crop for farmers, and were sold in larger quantities for use in traditional Chinese medicine. Later on, in the 12thC CE, good fossil fish were in such demand in China that they were routinely faked.

In the Classical world, also, there were many anatomical models made, of mythical beasts such as Centaurs, Tritons and man-headed snakes. Mayor argues that these were not always cynical fakes but at least sometimes powered by the same instinct which makes modern palaeontologists reconstruct creatures of which they have scant remains. Those who saw though these constructs sometimes did so for anti-scientific reasons: for example Palaephatus argued that Centaurs must never have existed, because species were fixed and if they had once existed they could never have gone extinct.

Aristotle’s ideas of the fixity of species did not go unchallenged, however, even in the west. The Roman philosopher-poet Titus Lucretius Carus, 99—55BCE, wrote a famous poem called De rerum natura, On the Nature of Things, based on the tenets of Epicureanism. In it among many other things he set out his own ideas of evolution. He believed that organisms formed from a combination of the elements and chance, then natural selection weeded out the less successful forms, and his idea that this was a blind natural process was influential in post-Mediaeval scientific thought.

However, he didn’t believe land animals could evolve from marine ones, and was dubious about one species evolving into another. He believed instead that all extant animals had been there from the beginning, even as other organisms went extinct all around them. He was also a firm believer in the already thoroughly obsolete and disproven idea of a flat Earth.

Evolutionary thought in the early post-Classical period

The widely-travelled 1stC CE Pythagorean philosopher and wonder-worker Apollonius of Tyana (c. 3BCE—97CE) is notable among other things for having tried to explain fossils rationally as functional animals. He suggested, for example, that griffins could not fly but might have had membranous wings that helped them to leap, which makes me wonder whether he had either seen a pterosaur fossil, or seen a Protoceratops which still had the imprint of skin on its neck-frill. He identified and described fossil ivory, and spoke of skulls of “dragons” – which he accepted as a still-extant species – seen on his travels in India. Unlike most of his predecessors he was able to separate factual evidence from mythological assumptions, stating that he agreed that giants once existed, because “gigantic bodies are revealed all over earth when mounds are broken open. But it is mad to believe that they were destroyed in a conflict with the gods”. In general, he counselled seekers after knowledge to pay attention to the evidence, but look for natural explanations for it.

But his words fell largely on deaf ears. His brother philosophers preferred abstract thought-processes to actual material evidence, while both the Roman priesthood and the new religion of Christianity generally preferred mythological explanations for it, although his contemporary Pliny the Elder (23/24—79CE) posited a vague sort of evolution, in that he could see that many ancient bones were very large, and took this as evidence that all natural life was slowly dwindling. He wrote an extensive encyclopaedia of natural history; described many fossils in detail, including small, un-exciting ones such as crinoid stems and sea-shells; and correctly identified amber as fossilised sap which had sometimes trapped once-living creatures as it oozed from the tree. Tacitus, (c. 56—c. 120CE), made the same observation about amber.

In the 2ndC Phlegon of Tralles (exact dates unknown) and the geographer Pausanias (c. 110—c. 180CE) continued to take an interest in and record fossil finds around the Mediterranean. Pausanias observed that “animals take different forms in different climates and places”. His descriptions of remains he had seen or heard about were level-headed and practical.

In the 2nd and 3rdC, the Greek-influenced Roman philosopher Claudius Aelianus (175—235CE), known as Aelian, was persuaded by popular myth and skillfull anatomical fakes to believe that Centaurs might once have been real,, but his reasoning about them was impeccable: that time and nature in the deep past might have generated strange fauna which were now extinct. Like many of the philosophers, he had the idea that there were strange creatures in the past which had died out, but not that the creatures of the present had not always existed. In the 3rdC, the sophist (something like an informal university professor) Philostratus of Athens (c. 170—247/250CE) wrote a life of Apollonius which contains most of what we know about him.

Many other Roman observers described fossils, and the presence of seashells where no sea now was, without reaching any conclusions about the past or the origins of ancient remains, other than “this bit used to be under water”. But intellectual enquiry was passing into the hands of the early Christian church, which at its inception was extremely science-positive, insofar as science could be said to exist at that time. Organised science-denial by Christians, as opposed to occasional moments of incredulity about specific discoveries which went against the accepted scientific wisdom of their time, is really a modern and almost entirely Protestant phenomenon.

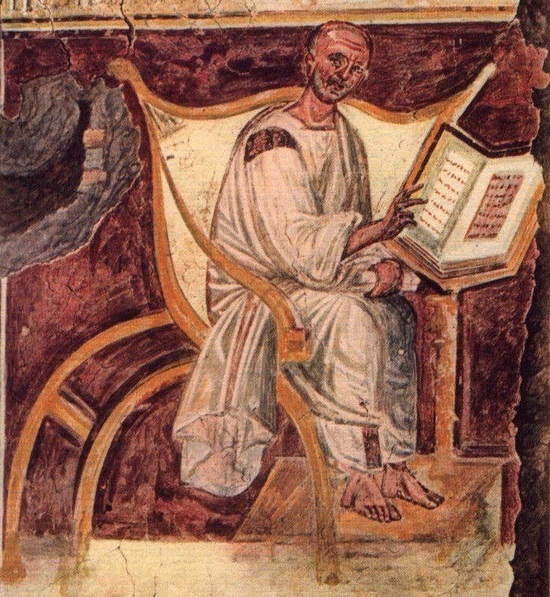

I have a separate article on the attitude of the Early Church Fathers to Biblical literalism, with full texts available for quoting. Origen (c. 185—c. 253CE), a.k.a. Origen Adamantius, the author of De Principiis, On the First Principles, the first-ever systematic treatise on Christian theology, wrote that no-one with understanding would take the Creation and Adam & Eve stories literally as written, and that “these things figuratively indicate certain mysteries, the history having taken place in appearance, and not literally”. I don’t know that he necessarily disbelieved the idea that God created the world and its life-forms over a short period, or that humanity began with a single divinely-generated couple, since no alternative scenario had really been proposed at that time: but he was emphatic that the details of the stories in Genesis were ridiculous if taken literally, and were clearly intended as educational parables.

St Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335—c. 395CE), bishop and theologian and a member of the influential group called the Cappadocian Fathers, is credited with being one of the founders of a more naturalistic idea of the origins of Earthly life. He believed that life was created by God, but emphasised that in the Biblical account life “proceeded by a sort of graduated and ordered advance”, from plants to beasts to humans, and that “the vital forces blended with the world of matter according to a gradation; first it infused itself into insensate nature; and in continuation of this advanced into the sentient world; and then ascended to intelligent and rational beings”. [Note that people often confuse “sentient” and “sapient” – sentient means conscious and aware of sensation, like all but the most simple animals, while sapient means capable of complex thought at a human or near-human level.]

Probably the greatest of all of them was the scholar, theologian and bishop St Augustine of Hippo (354—430CE), whose ideas had a huge influence on later Western philosophy and Western Christianity, and who is credited with having personally reinvigorated and re-established Christianity. He was so exercised about the stupidity of Biblical literalism as it related to Genesis that he wrote whole books on it, called De Genesi ad Litteram, The Literal Meaning of Genesis, and De Genesi contra Manichæos, that is, Genesis in Contradiction of the Manichaeans.

He stated that it was “disgraceful and dangerous” for a Christian to assert, on the basis of their understanding of scripture, things which ordinary people knew to be incorrect on the basis of reason and experience, as it made Christians look vastly ignorant, and caused anything they then said about religion to be laughed to scorn. He was a prophet, was Augustine, as well as a theologian. He wrote that “no Christian would dare say” that everything in the Bible should be taken literally, when clearly a lot of it was allegorical.

Regarding evolution, or something approximating it, he accepted Pliny the Elder’s opinion that life in general and humans in particular were growing smaller over time. As evidence he cited his own viewing of a human-looking but vast molar (probably from a mastodon). He stated that “. . . at least we know [the days of creation] are different from the ordinary day of which we are familiar” – that is, the “days” mentioned in Genesis could have been any length – and that “The things [God] had potentially created. . . [came] forth in the course of time on different days according to their different kinds. . . [and] the rest of the earth [was] filled with its various kinds of creatures, [which] produced their appropriate forms in due time.”

In other works, he speculated that “certain very small animals may not have been created on the fifth and sixth days, but may have originated later from putrefying matter”. This is probably related to the idea in later centuries that maggots were spontaneously generated by the decaying matter they fed on. We know now that animals – any animals – are much too complex to pop into existence through spontaneous generation, although we do believe that extremely simple proto-cells that were little more than complex chemicals once did so. Nevertheless it shows that Augustine, probably the most important person in the history of Christianity aside from Jesus/Yeshua himself and St Paul, believed that at least some organisms were not directly created by God, but evolved later through a natural process – even if his ideas about how that process worked were hazy.

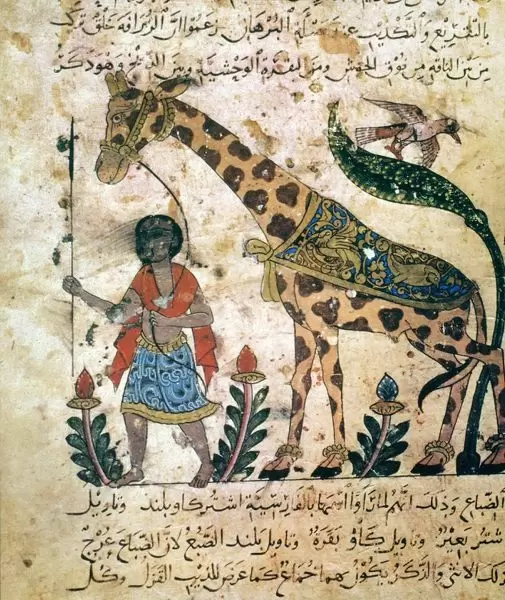

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5thC took with it most of Classical scholarship about fossils and early ideas of evolution, but some knowledge survived in Byzantium. Two hundred years later, some Islamic scholars took up the torch. Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī (776—868/869CE), known as al-Jāḥiẓ (Bug-Eyes), an Iraqi scholar of Ethiopian descent and impoverished background, wrote over two hundred books, of which thirty survive. His best-known work is the Kitāb al-Hayawān or Book of Animals, which combined a detailed bestiary with poems, jokes and anecdotes. In it he described food-chains and wrote that “Every weak animal devours those weaker than itself. Strong animals cannot escape being devoured by other animals stronger than they. And in this respect, men do not differ from animals”. According to mvslim.com, which quotes extensively from the Book of Animals, he went on to say that “Environmental factors influence organisms to develop new characteristics to ensure survival, thus transforming them into new species. Animals that survive to breed can pass on their successful characteristics to their offspring”. If that’s an accurate translation he had understood much of the basis of evolution, except for the radiation of species.

In the 13thC, St Thomas Aquinas (1225—1274), an extremely influential Italian Christian philosopher and theologian, proposed that God had created the potential for organisms which had then sprung up over time, not all at once; but he saw this as a divinely ordained and planned process.

In the 14thC the Muslim Tunisian polymath Ibn Khaldun (1332—1406) wrote a book of universal history called the Muqaddimah, in which he wrote that species became more numerous over time, and that humanity stemmed from “the world of the monkeys”. In the first chapter he wrote that “This world with all the created things in it has a certain order and solid construction. It shows nexuses between causes and things caused, combinations of some parts of creation with others, and transformations of some existent things into others, in a pattern that is both remarkable and endless.”

In chapter #6, he wrote that:

We explained there that the whole of existence in (all) its simple and composite worlds is arranged in a natural order of ascent and descent, so that everything constitutes an uninterrupted continuum. The essences at the end of each particular stage of the worlds are by nature prepared to be transformed into the essence adjacent to them, either above or below them. This is the case with the simple material elements; it is the case with palms and vines, (which constitute) the last stage of plants, in their relation to snails and shellfish, (which constitute) the (lowest) stage of animals. It is also the case with monkeys, creatures combining in themselves cleverness and perception, in their relation to man, the being who has the ability to think and to reflect. The preparedness (for transformation) that exists on either side, at each stage of the worlds, is meant when (we speak about) their connection.

So although Ibn Khaldun hadn’t arrived at natural selection, he had understood that species can transform into other species, and did so by some kind of progression.

It’s worth noting that the idea that humans were related to other primates was not a new one, although Ibn Khaldun might have been the first to say it in print. Usually, however, instead of expressing it as “humans are a type of ape”, it was viewed the other way as “all apes (and sometimes monkeys) are types of human”. Ancient Greek travellers spoke of creatures they called akephaloi, “headless ones”, later called Blemmyes or “men whose heads do grow beneath their shoulders”, described as men with no head and with faces on their chests, living in Libya or India. Some, reputed to live near the Brisone or Brixontes River, were said to have their eyes on their shoulders. Some were said to be cannibals. These stories persisted right through to the late Mediaeval period.

[The Brisone was believed to be a river south of Egypt and either parallel to or forking from the Nile: probably east of it because Blemmyes was the name of a real tribe in that area. It might have been based on the Blue Nile or on an oxbow lake spawned by the Nile, or might have been purely fictional.],

It seems pretty clear these were confused stories of non-human great apes, probably gorillas in Africa and orangutans in Asia, whose heads are carried very low, often seeming to be below the shoulders. “Orangutan” in Malayan means “man of the woods” (I’ve read that the common misspelling “orangutang” means “man in debt”!), and local legend has it that they can talk, but choose not to do so so humans won’t put them to work. Even fairly recent European travellers initially thought they were odd humans, until they got a very close look at them.

In the 5thC BCE, the Greek physician Ctesias wrote of cynocephalii, dog-headed men, living in India. Other Greek and Roman travellers also spoke of dog-headed men in India, while Herodotus said they lived in Libya.

Again, these ideas persisted right through the Mediaeval period in Europe, with the cynocephalii definitely seen as real creatures, and usually as a sort of human. Some of the Mediaeval descriptions, which have them wearing fur capes and painting their faces, make it plain the stories refer to macaques (some of which have dramatic manes) in India or to baboons, and especially to mandrills, in Africa.

Nor is this only an ancient or Mediaeval issue. The story may or may not be true, but it’s traditionally claimed that after a Napoleonic-period French ship sank off the English port of Hartlepool, the sole survivor was the captain’s pet, a monkey dressed in a miniature French uniform, who was promptly hanged as a spy by the townspeople. They believed that the French had tails, and so saw the unfortunate monkey as a small human. “Wha’ hangit the monkey?” became a traditional insult hurled at people from Hartlepool, and in response they called their football team the Monkey Hangers.

A basic idea of heredity and inheritance was also understood. For example, in 1540 Henry VIII decreed that no mare under 13 hands or stallion under 15 hands would be allowed to be loose on common land in England, and any undersized stallions found on common land would be killed, in an effort to increase the size of English horses. Then and later, farmers understood the principles of breeding for particular characteristics. The Jews also already had some vague idea of sex-linked inheritance, as it related to not circumcising a baby boy if there was haemophilia in his mother’s family

Renaissance and later evolutionary thought and the knowledge of Deep Time

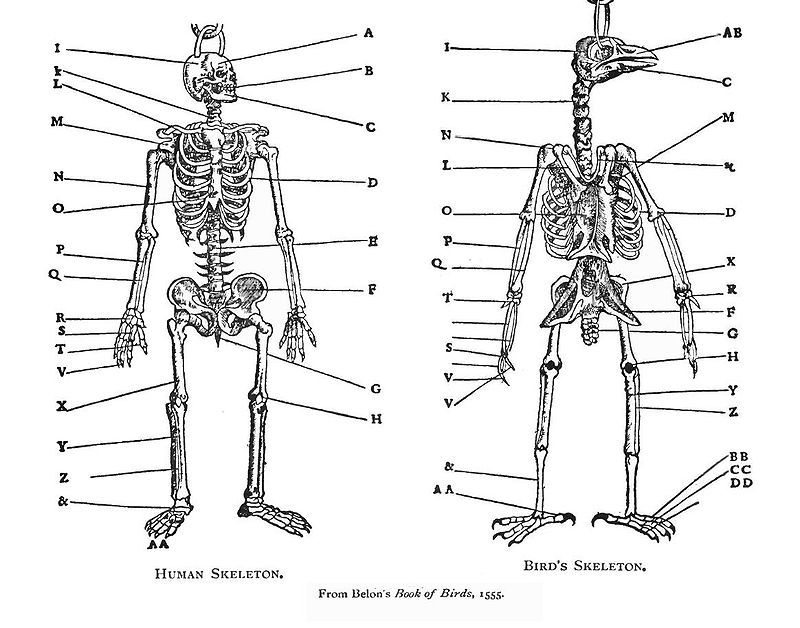

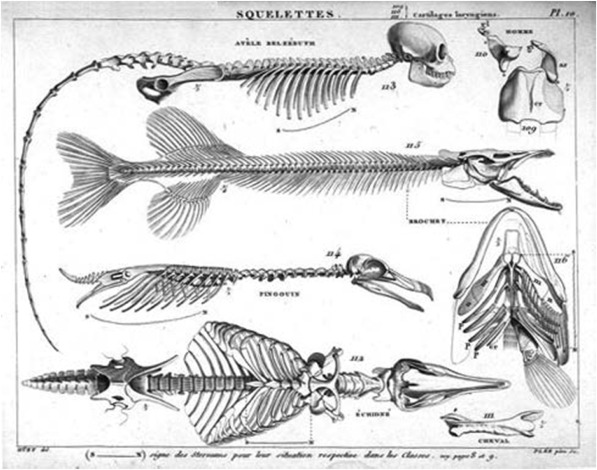

In 1555, the French naturalist Pierre Belon (1517—1564) published L’Histoire de la nature des oyseaux (The Natural History of Birds), in which he noted the skeletal similarity of birds and humans: an important step, although he probably didn’t realise it, on the road to understanding the radiation of species.

In the early 17thC, the French philosopher Renée Descartes (1596—1650) was influential in encouraging the idea that the universe ran like a machine, without needing to involve the intervention of gods. In many respects, however, his ideas were profoundly in opposition to evolution and in that sense far more primitive than those of religious thinkers such as Ibn Khaldun, for he believed that mankind was fundamentally different from all other animals, at least mentally, a different sort of thing, and that non-human animals were mere clockwork mechanisms with no consciousness, who could be subjected to any cruelty without remorse because they had no awareness of pain, and no self with which to be aware. His ideas had a poisonous effect on animal welfare, especially in the laboratory, for around 350 years.

The French aristocrat and diplomat Benoît de Maillet (1656-1738) equally believed that the world progressed by wholly natural processes, but had a much better grasp of the interconnectedness of life than Descartes had. He was the first known proponent of panspermia – the idea that the seeds of life drifted through space – and believed that plants came from seaweed and humans from fish (not too far from what we now believe) and also, less plausibly, that birds came separately from flying fish.

The great German mathematician and polymath Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646—1716) took a more theistic view. He saw the body and soul as separate entities which influenced each other. He believed that the soul was acting towards some final goal, but that “all corporeal phenomena can be derived from efficient and mechanical causes” – that is, that the body was acted on by short-term physical circumstances. This paved the way for what would later be the normal theistic view (normal in most countries except the US, Northern Ireland and hardline Muslim states) that bodies evolve through natural forces while being animated by a soul which has more metaphysical origins.

The French philosopher, mathematician and man of letters Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698—1759) was one of the first to think seriously about genetics and natural selection, suggesting that traits were inherited from both mother and father in combination to produce a new individual, and that only traits which offered advantages would be passed on. This, he thought, explained why all extant species appeared genetically fit (because they descended from those individuals who were fit enough to survive), and recognised that those extant species represented only a tiny fraction of all the species which had once existed.

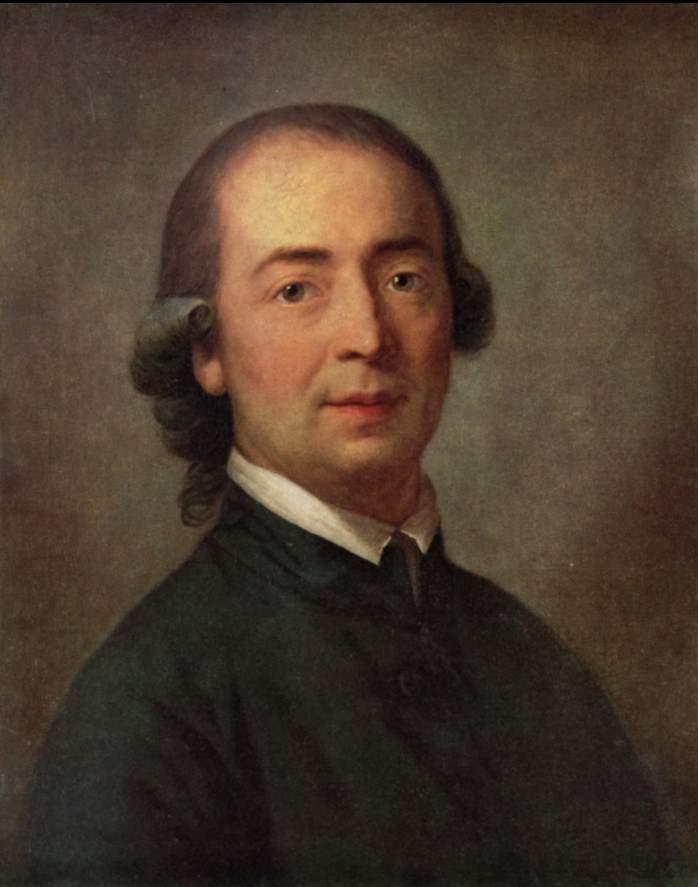

Like Leibniz, the Prussian philosopher, clergyman, poet and linguist Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744—1803) took a broadly theistic view, but is regarded as a strong Enlightenment precursor to Darwin. Between 1784 and 1791 he published a four-volume work called Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit (Ideas on the Philosophy of the History of Mankind) in which he wrote about the progression from simpler to more complex organisms over time, and the way in which nature produces an overabundance of species and individuals who then compete to survive. He understood the progressive development of life – but lacked Ibn Khaldun’s insight that humans were part of the same unfolding process.

He was however firmly opposed to racism, stating that despite their variations all humans were clearly the same species, and that nations which had persecuted Jews in the past had a duty now (i.e. in about 1780) to help them to regain their ancestral homeland in Israel. He wrote poetry about the injustice and cruelty of slavery as then practiced in the US, and held all human ethnicities to be equal; but in the 19thC his ideas on the distinctiveness of different peoples were perverted and used to prop up the very racism and African enslavement he had campaigned against. This is not a million miles away from where we came in, with Creationists willfully taking Darwin’s words out of context.

While this growth of early evolutionary thought was going on, however, taxonomists – scientists who sought to classify living things by species, genus etc according to their anatomical similarities – saw species as fixed and unchanging. The naturalist and botanist John Ray FRS (1627—1795) was the first to work out a coherent classification system for plants and was also the first to attempt to define a species, which he described as “as a group of morphologically similar organisms arising from a common ancestor”. But he also said that “. . . no surer criterion for determining species has occurred to me than the distinguishing features that perpetuate themselves in propagation from seed. Thus, no matter what variations occur in the individuals or the species, if they spring from the seed of one and the same plant, they are accidental variations and not such as to distinguish a species. . . Animals likewise that differ specifically preserve their distinct species permanently; one species never springs from the seed of another nor vice versa”, thus in his own mind ruling out the possibility of one species slowly transforming into another.

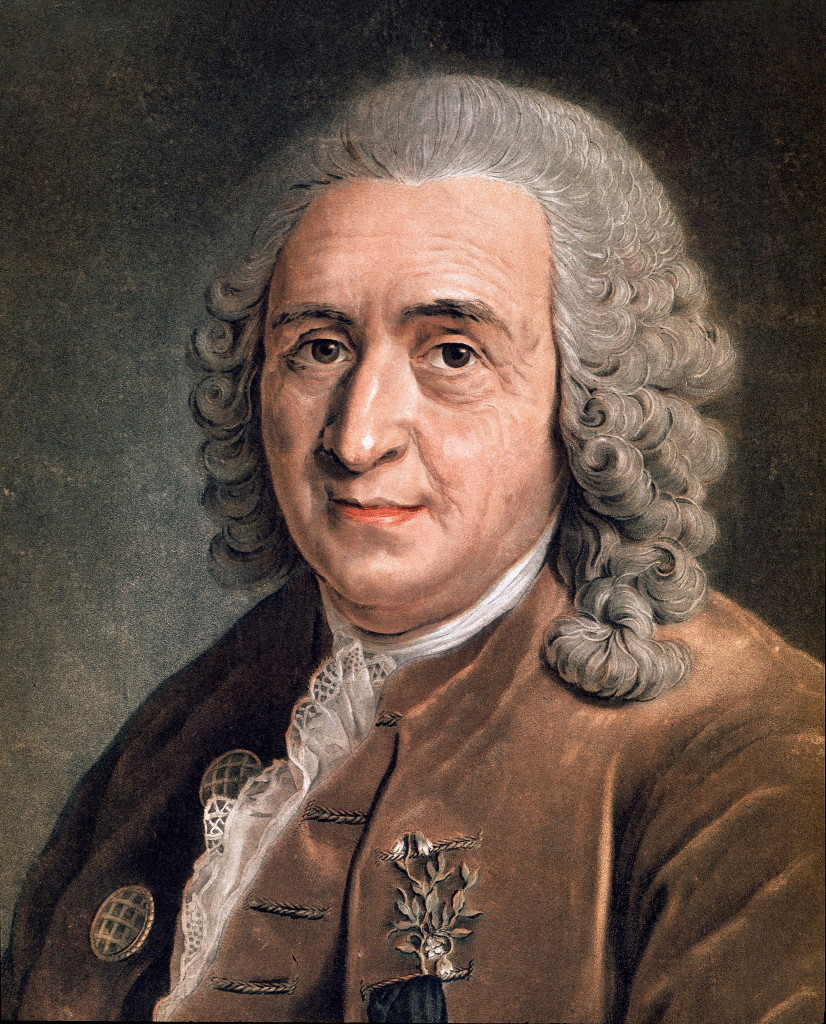

Perhaps these early taxonomists had some sense of the chaos which knowledge of evolution and DNA would bring to their discipline, making “species” and most higher groupings a decidedly woolly and often rather arbitrary concept. But the greatest of them, the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707—1778), the inventor of the binomial system of species names, couldn’t close his eyes to the obvious. In a letter to the German naturalist Johann Georg Gmelin dated 25 February 1747, Linnaeus wrote:

It is not pleasing to me that I must place humans among the primates, but man is intimately familiar with himself. Let’s not quibble over words. It will be the same to me whatever name is applied. But I desperately seek from you and from the whole world a general difference between men and simians from the principles of Natural History. I certainly know of none. If only someone might tell me one! If I called man a simian or vice versa I would bring together all the theologians against me. Perhaps I ought to, in accordance with the law of Natural History.

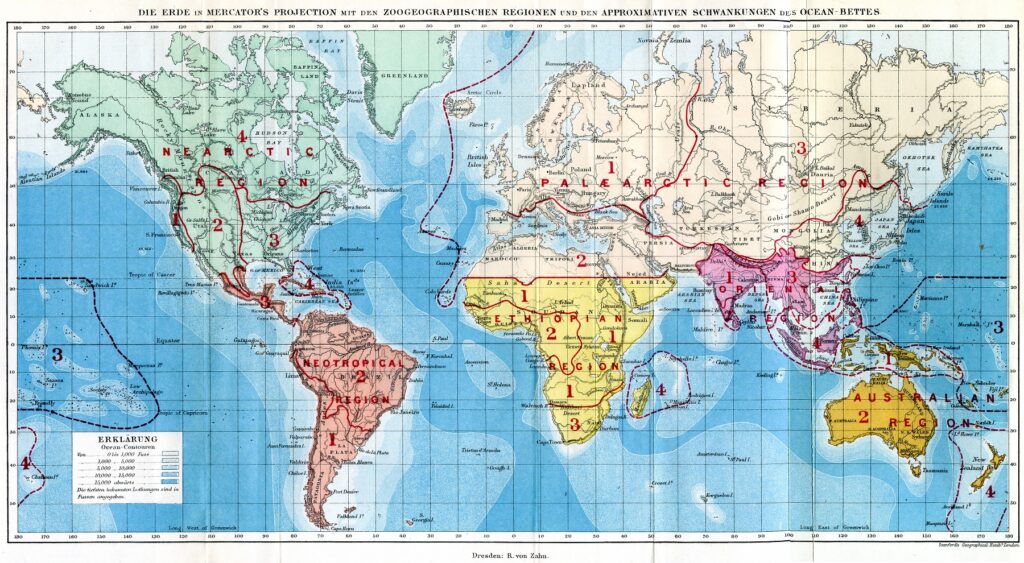

That “or vice versa” is interesting, because it suggests he was considering the Mediaeval and Classical solution of simply calling all apes and monkeys (that’s what “simian” means) exotic types of human. Linnaeus also had the idea that a new species would grow to fill the available space, but took it to extremes by proposing that all biota began at a single point with a single pair (possibly inspired by the Noah’s Ark story). This idea was ridiculed by German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann (1743—1815), who made the first detailed regionalization of the zoological kingdom, and thought it more reasonable to assume that God had created all species in the areas where they were now found, in large numbers and already in a balanced equilibrium.

The Genevan naturalist Charles Bonnet (1720—1793) was the first to coin the term “evolution” (which literally means “unrolling”), but he applied it to the since-discredited concept of pre-formation. This was the belief that organisms grow from microscopic copies of their adult form, tiny little complete organisms hidden inside the germ cells. This idea was profoundly opposed to evolution as we now use the term, for preformationists believed that these tiny homunculi had existed since the dawn of Creation.

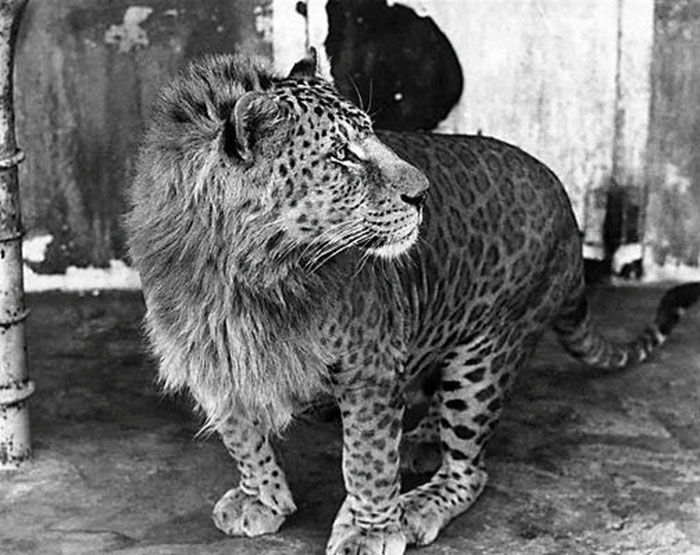

French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707—1788) got close to modern ideas of evolution, with some idea of adaptive radiation, and also “got” that species is a rather woolly and arbitrary concept. He suggested that what people were calling “species” were just extreme varieties, and that lions, tigers, leopards and domestic cats might have a common ancestor. This means that he had grasped the idea of adaptive radiation, and considering that lions, tigers and leopards can all interbreed and some of the hybrids are even fertile, he was really on to something. But he still denied that humans were primates and believed in what Creationists call “kinds”, groups of similar form which are wholly separate genetically from all other groups, even though his view of the world was materialistic and not theistic. He held that the 200 or so mammal species then known formed 38 discrete groups, each with a unique, discrete common ancestor originally formed by spontaneous generation, and shaped by “internal moulds” which prevented them from straying too far from the original. Remember that nobody at this time knew about genes or how inheritance really worked.

His fellow French philosopher and slightly younger contemporary, Denis Diderot (1713—1784), also believed that life arose through spontaneous generation (which we now think is sort-of true if you stretch the definition of “life” to include a lipid bubble with a wisp of RNA trapped inside), but held that species constantly changed as new forms arose and then survived or not through trial and error, getting ever closer to the idea of natural selection.

The Scottish judge James Burnett, Lord Monboddo (1714—1799), the founder among other things of the first Canongate theatre in Edinburgh, not only worked out the principles of evolution, but also applied them to the development of human languages (despite being partially deaf). He was an anthropologist, a nudist, a notorious eccentric and a friend of the great philosopher David Hume and of Robbie Burns, and had studied Greek philosophy at university, which probably helped open him up to the world of palaeontology. It had also left him amenable to believing in all kinds of odd creatures from Greek mythology, such as men with one foot (probably based on travellers’ tales of Equatorial African herdsmen who rest standing on one leg, like cranes – possibly because doing so forces them to stay awake and alert, otherwise they’d fall over).

He agreed with Linnaeus and Ibn-Khaldun that man was a primate, and was the first to understand that humans had started in a single location in a non-theistic sense (although he also suggested, probably as a joke, that human babies were born with tails which the midwife cut off). He understood that primates, and by implication other groups, had radiated from a common ancestor, and also proposed that creatures had changed their characteristics in response to their environment over a very long period; but because of his eccentricity and fondness for leg-pulls his ideas were not taken very seriously at the time.

Around a hundred years later, when Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published and causing a stir, Blackwoods magazine published a little poem which ran:

Though Darwin may proclaim the law,

And spread it far abroad, O!

The man that first the secret saw,

Was honest old Monboddo.

The architect precedence takes

Of him that bears the hod, O!

So up and at them, Land of Cakes,

We‘ll vindicate Monboddo.

Land of Cakes is a literal translation of Caledonia, the old name for Scotland. Scotland has been very important to the development of palaeontology and the concept of evolution, having an extensive, well-preserved fossil record, including many good dinosaur footprints, and a great deal of cruel and unusual geography much of which is on visible display, and some of it sticking up bang in the middle of the capital city.

James Hutton, (1726—1797), Scottish farmer and naturalist and the author of Theory of the Earth, is known as the founder of modern geology. He it was who observed the plasticity of rock, layered and folded and overturned, and understood the long time it would take to build up sediments. In the late 18thC, palaeontology was catching on as a discipline, but many people still saw fossils as evidence of Noah’s flood, and many people at that time were what we now call Young Earth Creationists and believed that the planet was only 6,000 years old. But Hutton said that when he examined the rocks of Siccar Point, a promontory about 20 miles east of Edinburgh, and of other geological sites, he found “no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.” This advance, the discovery of Deep Time, was vital to the development of evolutionary theory, as it demonstrated that the Earth was old enough to allow time for almost any transformation.

Many of his observations were made in Holyrood Park in Edinburgh. which contains a whopping-great extinct volcano right in the centre of the city. The rim of the volcano is known as Salisbury Crags, while a massive basalt plug in the shape of a crouching lion which sticks up at the south side of the park is called Arthur’s Seat. It was at a quarry at the foot of Salisbury Crags that Hutton observed where lava had forced its way between layers of sedimentary rocks, and said of it “We know that the land is raised by a power which has for its principle subterraneous heat, but how that land is preserved in its elevated station, is a subject which we have not even the means to form a conjecture.” The section of Salisbury Crags where he worked is known as Hutton’s Section in his honour.

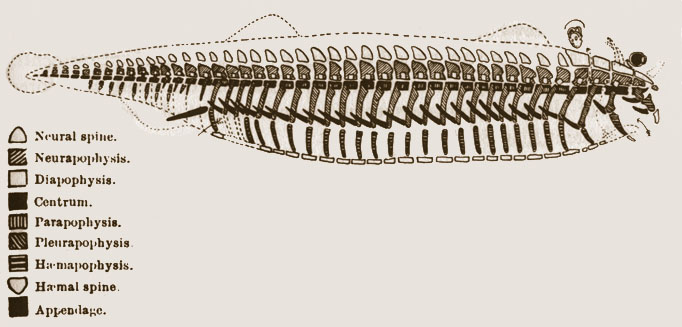

French naturalist Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (1769—1832), better known as Georges Cuvier, added another palaeontological advance by comparing the skeletons of mastodons and mammoths with those of extant elephants, and proving beyond doubt that species could go extinct. He could see that fossilised fauna came in layers characterised by different species, and was a believer in catastrophism – an extreme form of what we would now call punctuated equilibrium – with new ecosystems appearing after a succession of major geological changes which led to mass extinctions.

With somewhat less prescience, he declared that species were immutable and did not change over time, and that all large animal species had already been discovered and no new ones would ever be found – well before the discovery of the mountain gorilla, the saola (a fairly big Vietnamese bovine in between cattle and antelope) and at least a couple of species of beaked whale. In 1811 he and French geologist Alexandre Brongniart (1770—1847) published a study of the layered rock formations around Paris, which contributed to our understanding of palaeontology, but his opposition to the idea of evolution itself, as proposed by e.g. Lamarck and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (of whom more later), kept it out of the scientific mainstream for decades.

Separately, between 1799 and 1815, Cuvier and Brongniart’s contemporary William ‘Strata’ Smith (1769—1839) produced a geological survey of the area around Bath, and then went on to produce a very detailed geological map of most of Great Britain. This was the first detailed geological map of such a large area, and he was one of the first to use the different fossils found in different layers of rock as indices by which to distinguish those layers. Because he was of humble origins his work was largely ignored at first, but before he died he saw himself labelled as the Father of English Geology.

Also around this time, the English cleric and economist Thomas Robert Malthus FRS (1788—1834) was working on an idea of how population growth could lead to competition and a struggle for survival. His work An Essay on the Principle of Population was concerned with competition between human tribes, only, but it helped to shape the idea of natural selection in the minds of both Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace half a century later.

Erasmus Robert Darwin FRS, (1731—1802), was an English medical physiologist, a natural philosopher, an inventor, a poet, an ardent abolitionist opposed to the slave-trade, and Charles Darwin’s grandfather. His work Zoonomia: or The Laws of Organic Life, a two-volume work published in 1794 and 1796, was mainly concerned with associative psychophysiology (the idea that consciousness can be explained by the interplay of sensory stimulation and responses), but he also speculated that “all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament.” This is too limited – we now think that all life started from a filament of RNA, and that mammals and birds became warm-blooded separately – but it’s still startlingly prescient. His poem Temple of Nature, published (presumably posthumously) in 1803, described how all life arose from microorganisms in the mud.

You can read the whole thing here: Temple of Nature. It’s pretty heavy going: very flowery, and larded with breathless religious sentiment. But the accompanying notes are full of interest. For example, he says that the idea of spontaneous generation has fallen into disrepute because of Ovid and others suggesting that large animals could rise from the mud fully formed: but that “spontaneous vitality was only to be looked for in the simplest organic beings, as in the smallest microscopic animalcules”, foreshadowing our modern ideas about abiogenesis, and he predicts that these forms reproduced initially by parthenogenesis (“by solitary reproduction”), successively producing forms “rather more perfect than themselves” until they eventually developed sexual reproduction. He also used the term “evolution”, although not quite as we understand if today: he used it to refer to the unfolding of the world in general.

By now, at the dawn of the 19thC, evolution (although nobody was yet calling it that in the sense in which we use it now) was a hot topic, and as with his grandson, Erasmus Darwin’s ideas attracted some disagreement from Creationists. In 1802. so after the publication of Zoonomia but before Temple of Nature, the clergyman and utilitarian philosopher William Paley (1743—1805) published a work entitled Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity. It was intended in part as a rebuttal of Darwin Sr, accepting adaptation as real but seeing it as due to God acting directly through and on nature. Paley’s book was the first to draw the “watchmaker” analogy: the claim that any intricate system must have a designer. This of course was before the mechanism of evolution was known, let alone computer simulations which demonstrate how a simple algorithm can generate complex results. And who, at the time, could have expected that the same tired, long-discredited arguments would still be being dragged up in the US Bible Belt 200 years later?

Growing understanding of the mechanisms of evolution

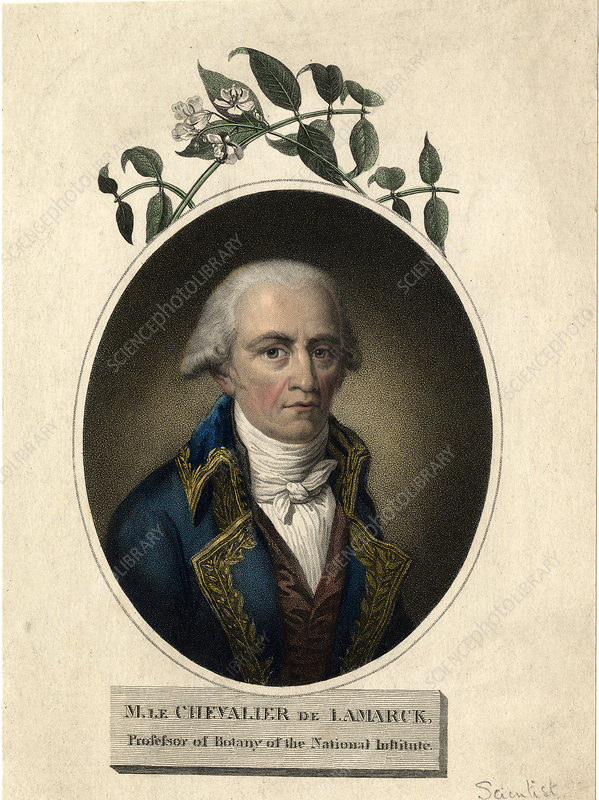

The time was now ripe for a serious scientist to work out the actual mechanism of evolution, rather than the mere fact that it happened. Unfortunately, the first person to do so was French naturalist and professor of botany Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1744—1829), who got some parts of it spectacularly wrong, even though his ideas seemed reasonable at the time. In his 1809 book Philosophie zoologique, Philosophy of Zoology, Lamarck started from the assumption that the transmutation of species was definitely real. He did not, however, believe that all life shared a common ancestor, but rather that simple life was continuously created by spontaneous generation, with each new instance of generation giving rise to a separate line of descent (or of ascent, depending on how you look at it).

This is actually not a million miles from modern ideas of abiogenesis, except that we now think that all known life is descended from the same common individual single-celled ancestor, or gene-sharing pool of single-celled ancestors, about four billion years ago. Any other simple cells which were not part of that common pool and which may have formed by abiogenesis at the time, or since, either died out without leaving descendants, or their descendants are small and obscure and live somewhere where we haven’t found them, such as on the deep ocean floor.

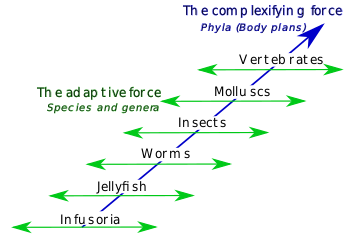

Lamarck proposed that all species were arranged on an ascending ladder of increasing complexity, a “great chain of being” in which organisms could be seen as “higher” or “lower”, similar to Aristotle’s scala naturae, and that there were two forces at work to generate this. The Complexifying Force was an undefined “life force” which caused organisms to move from simple to more complex over time (a sort of reversal of entropy). Within each level, the Adaptive Force resulted in the generation of the visible variety of species, as organs which were under-used atrophied and ones which were exercised increased. He called his and others’ belief in what we would now call evolution “Transformationism”.

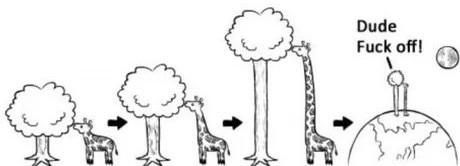

It was the mechanism which he proposed for this atrophy or increase which is now known as Lamarckian inheritance or Lamarckianism. In his view, transmutation happened within an individual’s lifespan. Since nobody yet had a very clear handle on how inheritance happened, although it clearly did, he thought that characteristics which an organism acquired during its life, by e.g. stretching or building up muscle, or by neglecting a body-part and allowing it to become weak, would become fixed in what we would now call its genome, and then passed on to its offspring.

We now know that this is incorrect in all but a few instances. Evolution in fact normally occurs through the differential reproductive success of organisms who were born already carrying the genes for inherited traits which make them better able to have healthy offspring in their environment, or to promote the welfare of the offspring of close relatives with whom they share the same genetic traits. When underused body-parts, such as the eyes of cave-fish, become weaker from generation to generation it’s because there’s no selection pressure to keep the genes which control them healthy, so they accumulate harmful mutations.

Lamarckian inheritance has been thoroughly discredited, except for a few very limited instances of which more anon. In the mid 20thC the Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko would decide that natural selection, genetics and science-based agriculture were Western conspiracies and reject them in favour of Lysenkoism, which combined a souped-up version of Lamarckian inheritance with wishful thinking. Biological science in the Soviet Union was destroyed for decades as a result, leading to the failure of Soviet agriculture and contributing to the ultimate collapse of the Soviet system.

There are two limited exceptions we know of, however, where acquired traits are passed on in much the way Lamarck proposed. Epigenetic tags are formed when an organism is subject to stresses during its life which result in changes in the histone scaffolding which supports the chromosomes, affecting how frequently particular genes get expressed, and these changes can be passed on for a few generations.

It’s also the case that individual genes, stretches of nucleotide bases, can be read in slightly different ways depending on where you start, resulting in different strands of mRNA being generated and different proteins manufactured from the same gene. Octopodes carry this to extremes, making their genes do the duty of Swiss Army Knives, and they seem to be able to change which mRNA is produced with what frequency during their lifetime in response to environmental pressure, with some kind of behavioural input, and then pass that on to future generations without necessarily changing the original genes. We’re still working out how the creepy little fuckers do it.

Contemporary with Lamarck, the Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle (1778—1841) wrote about what he described as “Nature’s War”, the struggle for existence between competing individuals and species. Plants, he wrote, were “at war with one another” for space and resources. He was the first to recognise the principle of convergent evolution, where different species could come to have similar characteristics which had not been possessed by their most recent common ancestor, and understood that there must be historical reasons why similar habitats in different regions were inhabited by different species. He understood the importance of homology, where organs which might now have different functions clearly shared a common origin (like the similarity between human and bird skeletons detailed by Belon 250 years earlier), and used the organisation of the different organs of plants to classify their relationships.

Sir John Saunders Sebright (1767—1846) was not a geologist or palaeontologist but an expert on animal husbandry, but his ideas were to impress Charles Darwin. In a pamphlet published in 1809, Sebright wrote that “A severe winter, or a scarcity of food, by destroying the weak and the unhealthy, has all the good effects of the most skilful selection” so that “the weak and the unhealthy do not live to propagate their infirmities” – explicitly comparing the effect of natural competition and environmental pressure to human-led selective breeding. He was also the developer of the Sebright bantam chicken. This is a small, neat-looking bird which usually has white or tan (“silver” or “gold”) feathers outlined in black, although dilute forms, where the edging is just a darker shade of the ground colour, now exist..

In 1813 Scottish-American physician and printer Dr William Charles Wells FRS FRSE FRCP (1757—1817) presented various papers before the Royal Society (the UK’s national academy of sciences, founded in 1660), starting from the basis that evolution had occurred in humans, and then describing natural selection (although he didn’t use that term) in relation to skin colours in humans. In 1818 a similar paper of his entitled An Account of a White Female, part of whose Skin resembles that of a Negro, with some observations on the cause of the differences in colour and form between the white and negro races of man was published posthumously (the lady in this case was “white” in the most literal sense – she was an albino).