[Note this is a work in progress: there’s still more information to find, especially as there’s a collection of Gray’s letters in the Seven Stories archive in Newcastle.]

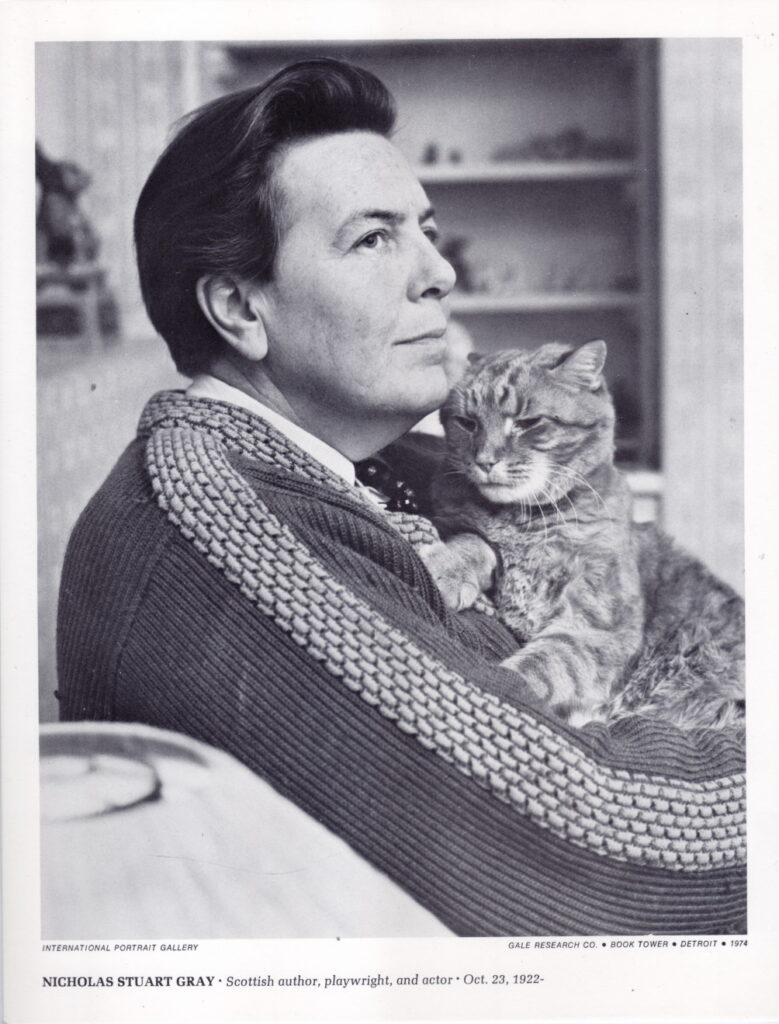

Nicholas Stuart Gray, Nick to his friends, was in his day an extremely well-known children’s playwright and YA fantasy novelist, a successful actor, director and stage manager and a less successful, but still published, illustrator and poet. His first professional play was reported to have been produced when he was just seventeen and he appeared numerous times on TV, both as an actor and as a writer. Between 1940 and 1979 he published twenty-seven books and illustrated at least one more, as well as composing five more plays which were performed but not published. There may be more illustrated books I don’t know about, for in 1968 the Coventry Standard called him “a well-known illustrator of books”.

Current or future Big Name stars such as Derek Jacobi and Patrick Troughton appeared in his plays. Often, five or six productions of Gray’s plays were all playing across the UK simultaneously during the Christmas/New Year season and several more in other countries; especially in the 1950s before anyone else had got in on the “proper plays for children” gig. During 1956, for example, there were at least twenty productions of his plays worldwide, and for at least twenty years he was universally regarded as the author of children’s Christmas plays: indeed in 1966 The Stage said that “One of the delights of Christmas is always the Nicholas Stuart Gray play for children”. On at least one occasion the same play by him was being performed by two different theatres in the same English town at the same time. And this is just the ones that were produced in English: his works were also translated into and performed in many other languages.

Yet now, all of his works except one play (The Other Cinderella) and one short story (The Star Beast) are out of print. This is both surprising and regrettable, given that he has been acknowledged as an influence on many modern fantasy authors. Hilari Bell, Cecilia Dart-Thornton, Kate Forsyth, Cassandra Golds, Ellen Kushner, Katherine Langrish, Sophie Masson, Garth Nix and Terri Windling all recall him as a writer they enjoyed as children, and Neil Gaiman, no less, describes him as “one of those authors I loved as a boy who holds up even better on rereading as an adult” and as “unfairly forgotten, but … at his best, one of the most brilliant children’s authors of the 20th century”.

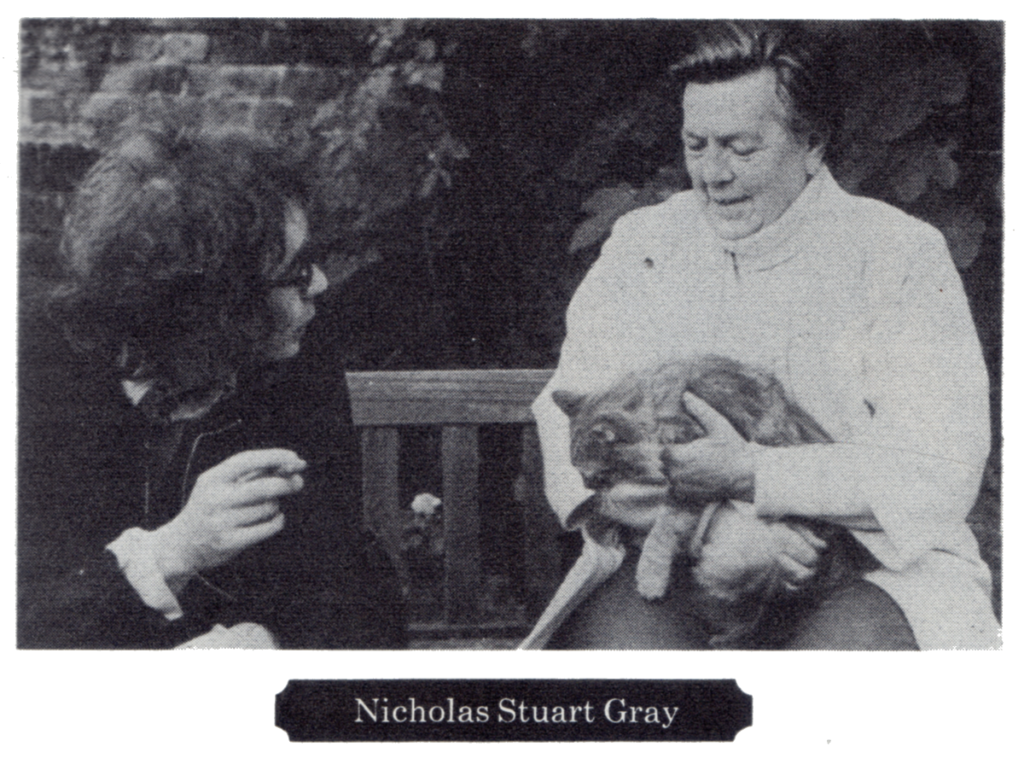

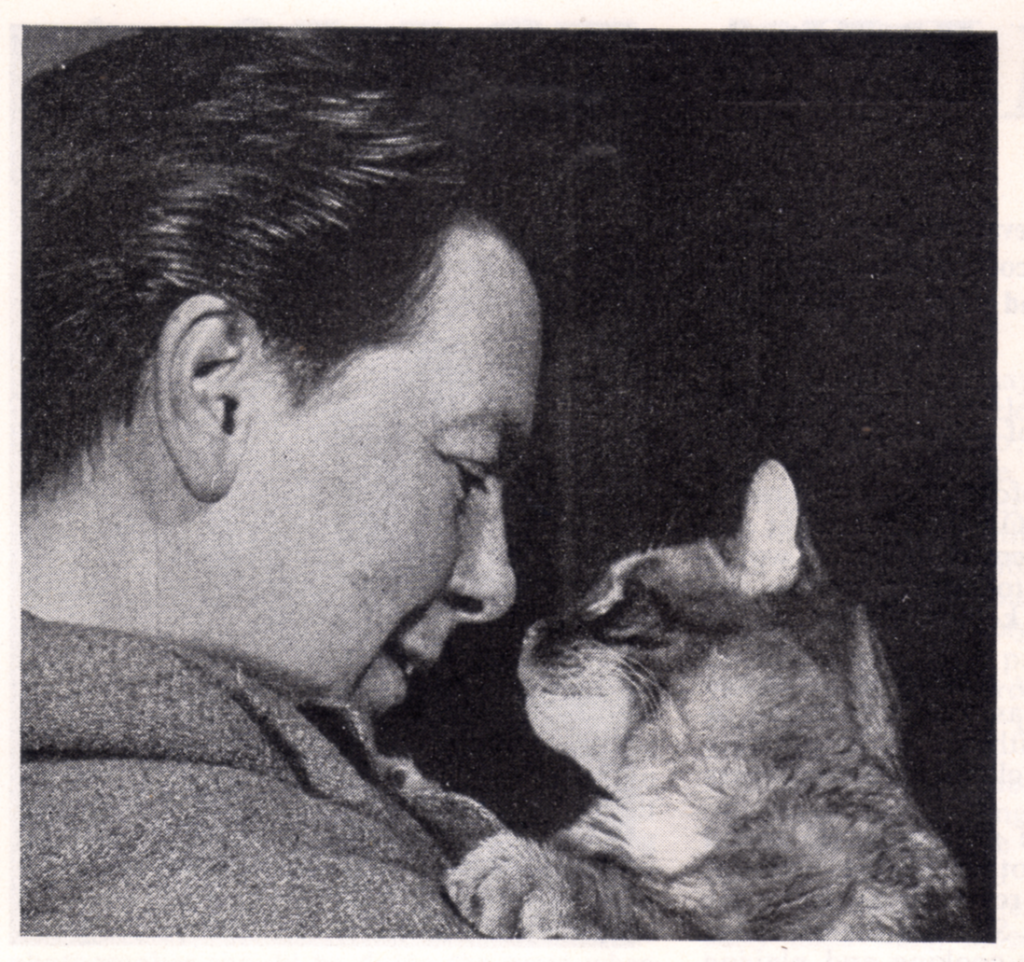

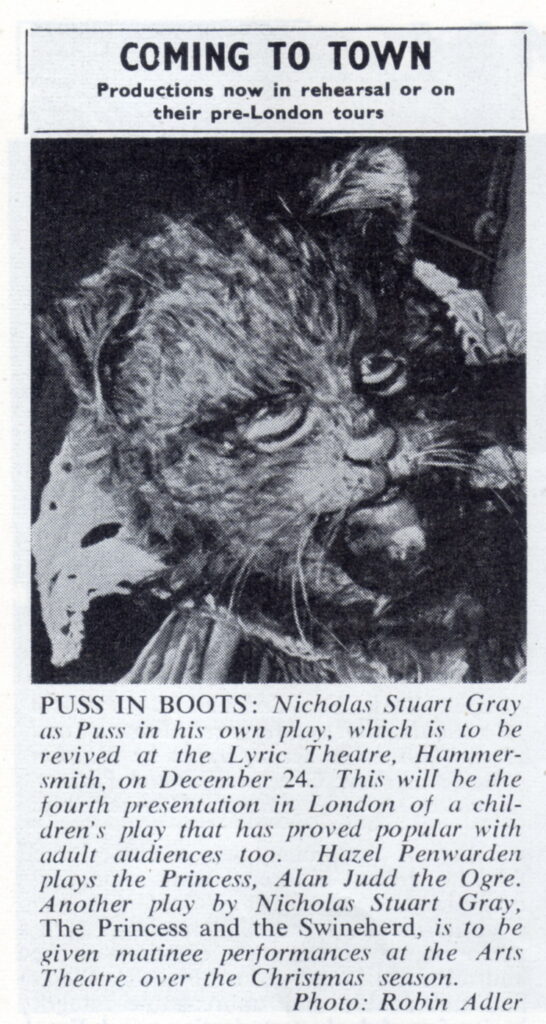

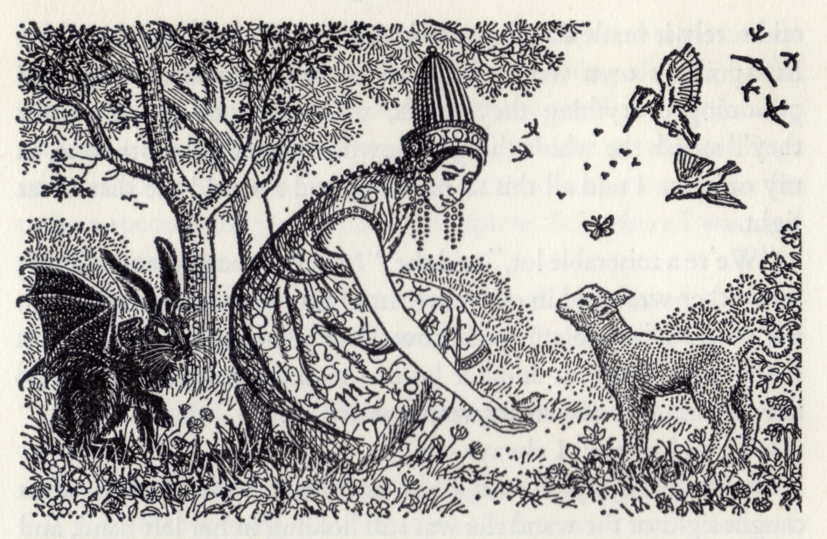

In a letter to The Times on 8th April 1981, shortly after Gray’s death, British children’s writer Geoffrey Trease said of him: “He wrote gracefully and wittily … blending much humour with deeper undertones of compassion. In our all too few encounters I found him a charming friend and excellent company, but with some of that feline reserve exhibited by his own Puss in Boots, a part he played with immense empathy, a stage cat to remember.” His influence is still felt today: Garth Nix has stated that his cat/god/demon character Mogget was inspired by Gray’s cats, and I suspect Gray likewise inspired Gaiman in specific as well as general ways. Good Omens, by Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett, has definite echoes of some of Gray’s work: the play The Other Cinderella revolves around a demon and a good fairy who are officially meant to be vying for control of human souls but are secretly friends and collaborators, a lot like Crowley and Aziraphale; and the episodic novel The Garland of Filigree features a demonic hound called Gytrash who decides that he is more dog than demon – again, decidedly reminiscent of the hell-hound called Dog in Good Omens.

[And one of the characters in Gray’s first novel Over the Hills to Fabylon is a Colonel Baldric – just sayin’.]

Gray was interviewed for the 1974 book The Pied Pipers: Interviews with the influential creators of children’s literature, edited by Justin Wintle and Emma Fisher, the interview being marked Hampstead, 1973. In this book he was grouped with still-acknowledged greats of children’s literature such as Rosemary Sutcliff, Alan Garner, Joan Aiken, Madeleine L’Engle, Richard Adams, EB White, Edward Ardizzone, Charles Keeping, Lloyd Alexander, Leon Garfield, Dr Seuss, Rumer Godden, Roald Dahl and Maurice Sendak, as well as a few who are less remembered, such as Scott O’Dell. His relatively early death from cancer seems to have sidelined him, perhaps along with the fact that so many of his works were plays for children, and therefore seen as either less accessible or less mature.

However, these are plays to be watched by children but performed by adults, with complex themes and dialogue and what the Sydney Morning Herald called “a light and supple whimsicality”. The Birmingham Post said in 1955 that “No other writer of our time has made so imaginative and sustained a raid upon a form of ‘juvenile drama’ that elders enjoy as much as the children”. Even the stage directions are eminently readable and show a bouncy, slightly biting wit – for example the leonine Beast is described as “beautiful, if you like that sort of thing”, and the demon in The Other Cinderella is “very handsome, in a dubious way”. The latter begins with the demon speaking in really clumsy, clunky verse – and then that turns out to be an actual plot point, as the forces of nominal good and evil are compelled to act out pantomime roles which are gradually drifting out of whack. As John Townsend, reviewer for The Manchester Guardian, said of New Clothes for the Emperor, “The dialogue is lively and the stage directions even livelier.”

Cassandra Golds not only cites Gray as a major influence and describes Down in the Cellar as “far more perfect a work than any of the Narnia books (powerful as they are)”, but also says that “I remember feeling a kind of mysterious desolation, partly because I’d finished it and would never be able to read it for the first time again, but partly also because I knew I had now read the best book I was ever going to read.” Sophie Masson on Fire Bird Feathers said of The Stone Cage that “The characterisation is superb, the dialogue crisp, the pace good, the combination of light and dark subtly achieved. And the beauty of the style! Fluid, graceful, it is humble—in that it doesn’t draw attention to itself—and yet it’s fresh, distinctive, individual … It was all so natural, so flowing, so multi-layered, its world richly imagined, yet delicately evoked … a novel just about perfect both in concept and execution”.

For myself, I consider Gray’s gentle, dreamy boys and tough, enterprising girls (written decades before that became the norm), his compassionate understanding towards even the most difficult characters and his witty, elastic prose to have been a major influence on both my world view, my sense of what it meant to be a woman and my prose style. I credit Gray and my late mother equally for the understanding that men are as vulnerable and as in need of care as women, which has led me to a lifetime of supporting male abuse survivors; and he is responsible for one of my all-time favourite quotes, which helped shape my attitude to reality itself. On the subject of whether or not to believe in magic (in the story, and by implication in psychic/occult phenomena in real life), one of his characters says: “Them as believes nothing, is seldom disappointed. But they do miss a lot of action!” I decided early on that I wanted to be in on whatever action was going.

Sophie Masson also said something else, though, in her essay on The Stone Cage. Of Gray himself, she says: “This was not a man who blew his own trumpet, not a writer who sought publicity, but one who loved his work and felt privileged to be doing it, and who was too humble to thrust himself forward. Who was perhaps also at heart a rather private, reserved, even secretive person, despite his long association with theatre, which many people would consider the home of trumpet-blowing, egotistical extroverts. Certainly, when I went to research his life, I found precious little information.” Indeed, Neil Gaiman has been advertising on his blog for years for any biographical data on Gray, without success, and there seems to be no mention of any kind anywhere of a Nicholas Stuart Gray existing prior to the late 1930s. As it turns out, there’s a very good reason for that.

According to most official accounts of his life Gray was born in the Highlands of Scotland on 23rd October 1922, to William Stuart Gray and Lenore May Johnston or Johnson, and died on 17th March 1981 (although the Pied Pipers interview said he was born in 1923, and his obituaries in The Times, The Stage and Locus Magazine, the primary newspaper of the science-fiction and fantasy scene, all said 1919). But although Gray described himself as a Highlander he certainly spent most of his life in England, and set many of his books in the south of England. I could find no record of his birth in Scotland, so then I went to the Free BMD site, which gives you a basic summary of births, deaths and marriages in England and Wales, from which you can go on to order a detailed certificate: but that wasn’t much better. There was one Nicholas C Gray born in autumn 1922, but his mother’s maiden name was Wardle.

So, from there I thought maybe I could get Gray’s death certificate, because that would tell me where and when he was born. I pulled up the summary of his death on Free BMD and saw that it said he was born in 1912. My initial thought was that either this was an error, or he had lied about his age and made himself ten years younger just because actors tend to be vain, but now I definitely wanted to check his actual death certificate, so I sent away for a copy.

His death certificate showed that he was indeed born in 1912, in London, and died on 17th March 1981 at the Royal Free Hospital in Camden, certified by SE James MB. There’s no doubt it refers to the right Nicholas Stuart Gray, because it gives his occupation as “Author and Actor”. It also gives his cause of death, which is listed as “a) Bronchopneumonia; b) Carcinomatosis; c) Ca Ovary (*NB Sex Change 1959)”. That is, his immediate cause of death was pneumonia, associated with widespread metastases (tumours throughout the body), associated with ovarian cancer which, since it’s mentioned separately, is presumably where the cancer started.

His sex at death is given as male, despite having at least one ovary, so he was evidently born transsexual or otherwise intersex. The fact that his sex change is presented as an explanatory comment on the diagnosis of ovarian cancer suggests that the change was from female to male. If the change had been the other way, if he had been born with ovaries but assigned as male at birth, it would probably have been considered a misidentification, not a sex-change; and in any case we know he lived as a man and had done so for decades, so any sex change had to have been towards being male, not away from it.

In 1959 he evidently had an official sex-change such that he was now considered medically male, but sadly it did not involve removing his ovaries (probably because he was already in his late forties and at or close to menopause), and he died at least partly of ovarian cancer at sixty-eight. He must have been among the first people in the world to have an official F2M sex change, as the first effective F2M gender reassignment surgery was only developed in 1951, and Gray had his in 1959. We can probably assume that he took masculinising hormone supplements prior to having the official sex change, as a photograph published in 1955 shows him already with a receding hairline: although it’s also possible he was a mixed-sex chimaera (a fusion of two fraternal twin embryos of differing sexes), and made his own hormones because he had both one ovary and one internal testicle which was overlooked at birth.

Gray’s death was registered by Winifred May Hatch, his sister. I already knew from WATCH (Writers Artists and Their Copyright Holders) who had inherited Gray’s copyright. Rights in his royalties were divided into four equal parts, for: Winifred M. Hatch, Robert Dudley Hatch, Arthur Maurice Hatch, and Joan Jefferson Farjeon (who was his friend, illustrator and set/costume designer). His copyrights were divided into five equal parts, for: Winifred M. Hatch, Robert Dudley Hatch, Arthur Maurice Hatch, Joan Jefferson Farjeon and Anderida Hatch. At this point I was still generally assuming that “Gray” was Nick’s birth surname, rather than a pen-name, that Hatch was his sister’s married name and that Robert and Arthur were her sons, but I looked up Robert Dudley Hatch (since it was an unusual enough name that there were unlikely to be two of them) and found that he was born in 1921. That meant he had to be either Gray’s brother or his brother in law; but then I found an entry on Ancestry which said that Robert’s mother was Lenore May Hatch, the same first and middle name as Gray’s mother.

Armed with this information I was able to find a 1921 census entry for the family which gave their approximate dates of birth, and from there I was able to get deaths as well. Arthur William Loriot Hatch (born in Brighton in 1880, d. 1944) and Lenore May Watson (born in Leytonstone in July 1882, d. 28th May 1965) had four children: Phyllis Loriot Hatch, born in Sydenham in South London in October 1912; Arthur Maurice Hatch, born in Hendon, Middlesex in or around March 1914, d. 1986; Winifred May Hatch, born in Branksome in Dorset in or around February 1919, d. 2005; and Robert Dudley Hatch, who was born shortly after the census in Croydon on 12th July 1921, d. Taunton Deane, Somerset in 1998. [Note: information from family members, acquired some months later, is that Arthur Maurice and Robert Dudley normally went by their middle names, at least within the family, and were known as Maurice and Dudley.]

We know from his own interviews that Gray was the eldest of four children, comprising himself, a sister and two brothers, and we know Winifred was his sister and that he left royalties and copyrights to her and to Arthur and Robert (and to Anderida Hatch, Arthur Maurice’s daughter, born in the last quarter of 1963 and evidently the nine-year-old niece Gray mentioned in his Pied Piper interview in 1973). Free BMD showed that the birth of Phyllis Hatch, mother’s maiden surname Watson, was registered in Lewisham in the December quarter of 1912, and for the sake of completeness I sent off for a birth certificate and confirmed that this was indeed Phyllis Loriot Hatch and that she was born on 23rd October, Gray’s birthday. There’s no record of a twin brother born the same day, or of any male Hatch born to those parents other than Arthur Maurice and Robert Dudley, so it seems clear Nicholas Gray is the same person as Phyllis Hatch.

Had the society of the day been accepting of trans people he would probably have settled for calling himself Phillip or Felix Loriot Hatch, but as things were he wanted to distance himself from his initial, female name, whilst preserving some connection with his family. So, he changed his father’s name from Arthur William Loriot Hatch to William Stuart Gray, his mother’s name from Lenore May Watson to Lenore May Johnston (Johnston being her mother’s maiden name), and his own from Phyllis Loriot Hatch to Nicholas Stuart Gray. He kept the part where he had a middle surname inherited from his father, and he kept both parents’ first names (apart from losing the “Arthur”). Why “Gray”? Maybe because hatching is a way of making greyscale in art using black ink, which he would know because his sister Winifred grew up to be a commercial artist. Also, because he was using his new name to live as a man whilst still, for the moment, anatomically female, he might have been making a rather dark joke about the traditional saying “All cats are grey in the dark”, explained by Wiktionary as “Sex is enjoyable regardless of the physical attractiveness or social station of one’s partner.”

The Scottish connection isn’t entirely bogus. Although his mother was born in Leytonstone in Essex, her father Thomas Watson was from Leith and her mother Helen Johnston from Aberdeen, so Nick’s Scottish heritage was genuine, although “Highlander” is a bit of a misnomer – it sounds like he was more of a teuchter (that is, from the Buchan lowlands of the north-east). His parents married in Scotland on 22nd April 1911 at 19 Polmuir Road, Aberdeen, “After Banns: According to the forms of the Established Church of Scotland”, and he may well have grown up mistakenly believing he’d been born there. Both Arthur and his father Alphonse are listed in the marriage register as cork merchants, and Arthur normally resided at 27 West Heath Drive, Hampstead (where he lived with his parents Alphonse and Helen and his slightly younger sister Helen Marguerite Hatch, a violinist) – although West Heath Drive is really more Golders Green than Hampstead.

Lenore meanwhile was an orphan (both parents dead, father Thomas Watson listed as a provision merchant), residing at 19 Polmuir Road and working as a hospital nurse. How they met, when they normally lived so far apart, is lost to history; but a Helen Hatch, presumably either the mother or the violinist sister, was a witness at the wedding in Aberdeen, so perhaps she and Arthur had gone there for some reason connected with the sister’s musical career. 19 Polmuir Road was a Nursing Home (at least it was in the 1930s), also referred to as an Old Persons’ Home, so there was probably a chapel for the residents, and Lenore was apparently “living in” at the time of her marriage. Probably it had a Nurses’ Home attached.

Lenore evidently grew up in Scotland, as she was born in 1882 and is listed as living in the Old Machar area of Aberdeen in the 1891 census (as Lenore May) and 1911 census (as Lenora May). She’s not in the 1901 census, but she was eighteen and was perhaps away at nursing school. On 8th February 1893, page 6 of the Aberdeen Weekly Journal and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland records Lenore May Watson as one of four girls chosen by the Aberdeen Educational Trust from a list of twenty-nine applicants to fill vacancies in a list of “outdoor foundationers”, entitled to an annual allowance of £12, with school fees and books.

As at the 1891 census Lenore was eight years old and living with Helen Johnston, her grandmother (widowed, sixty-one, herself born in Aberdeen), who had private means, along with an older brother Robert S Watson (ten) and a younger brother Thomas S Watson (six), who like her were born in England (did that recurring middle S stand for “Stuart”? – some day I might fork out the money for their birth certificates to find out). It looks as though her parents moved to England and then died when Lenore was between two and eight (and indeed, a Helen Johnston Watson of the right age died in late 1888 in West Ham when Lenore was six), sending their children to the maternal grandmother in Aberdeen. At the time of the 1911 census, just before Lenore’s marriage, she was living in or visiting the household of her uncle Peter Beveridge, a linen merchant, living with his wife Mary (presumably it was Mary who was the blood relative), three female cousins aged from eighteen to twenty-five, Peter’s brother Robert, and one servant.

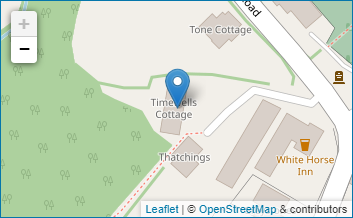

So, Nick Gray just swapped the names around a bit and stuck “Stuart” onto his father’s name to accentuate his own fairly genuine Scottishness, although his father’s family were Anglo-French: his father’s name was Alphonse James Paul Hatch, and Alphonse’s parents were William Henry Paul Hatch and a French lady named Francoise Anne Loriot. And in later life Gray valued his Scottish connection enough to have a second – or rather a third – home on the Isle of Mull.

Had Gray not died partly of ovarian cancer, his doctors would probably not have felt the need to note his sex-change on his death certificate, and it would have been much harder to track his origins down. I might well still have found his family through the fact that Winifred Hatch was his sister, but might never have realised that Phyllis and Nicholas were the same person, rather than a pair of twins one of whom was absent from home on the night of the census.

Of course, if he was a mixed-sex chimaera, rather than transgender, that would mean that Phyllis and Nicholas really were twins – but merged.

And of course, the recent publication of the 1921 census has been a tremendous help. I knew that Nick Gray’s sister’s surname was Hatch, but it’s quite a common surname, so without the census it would have been extremely hard to work out which Hatches belonged to the right family. As at 1921 their father Arthur William Loriot Hatch was a cork merchant with his own business and staff, and also an inventor (in 1927 he patented a new rear-viewing system for cars). Interestingly, a search of the newspaper archives shows that an A.W. Loriot Hatch of London, which is surely him, was heavily into amateur dramatics when he was in his twenties, a few years prior to his marriage. He appears to have given it up after 1909 – but that could just mean he moved to a new district whose local newspaper didn’t have an arts correspondent. He mainly appeared with the Dartmouth Dramatic Club which, since it was in London, must have been in the Dartmouth Park area, quite near Hampstead where he was living in 1911, and with shows in South London near what I discovered was his business address.

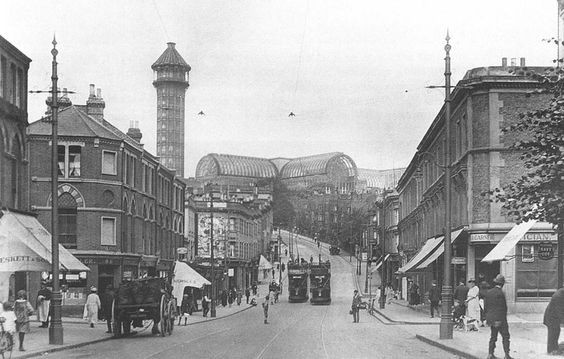

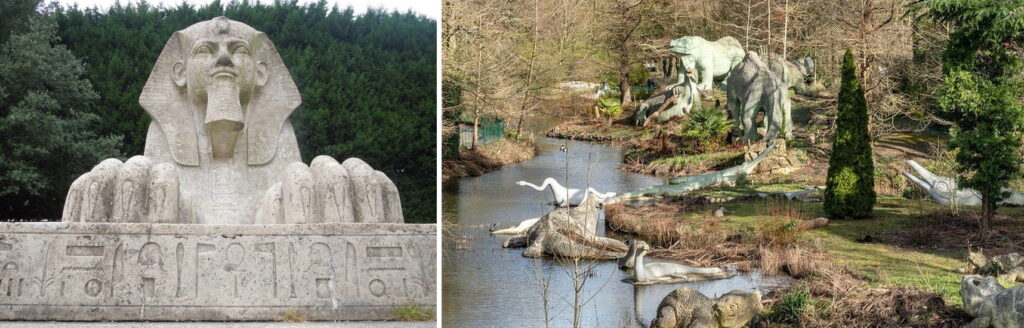

As a married man he was heavily involved with a tenement which his father Alphonse owned at 200 Borough High Street in Southwark, which seems to be where their cork business was based, and when he voted he evidently did so from his business address. In 1921 the family were living at 13A Weighton Road, Anerley (since replaced by a modern housing estate and flats), which means that Grey grew up within a short uphill walk of the original Crystal Palace, where the vast, glittering glasshouse and the towering Brunel water-towers which stood at either end of it dominated the skyline.

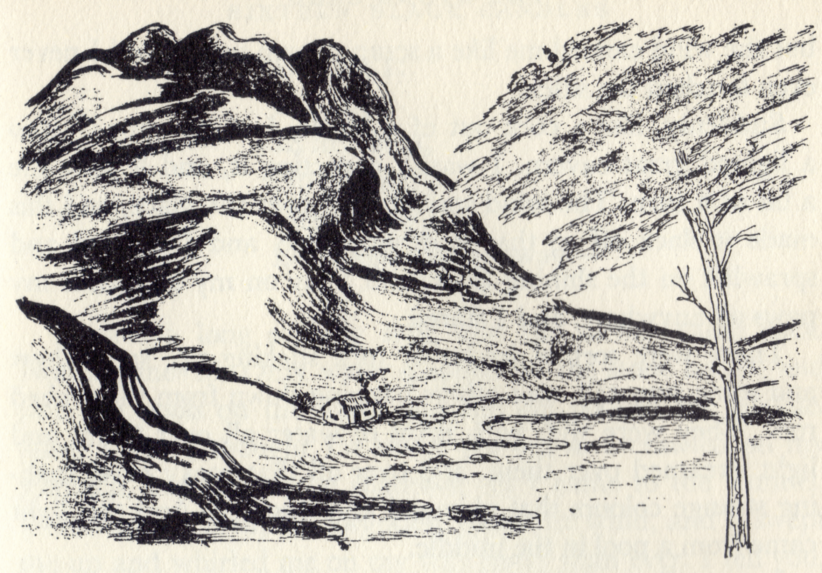

This massive entertainment and exhibition space was originally used for a World Fair in Hyde Park in 1851, relocated to Penge Peak (later just referred to as Crystal Palace) near Sydenham in 1854, and destroyed by fire in 1936. The young Phyllis/Nick must have been familiar with its impressive vistas and its mythological statuary, and the life-sized but not very accurate early Victorian plaster models of dinosaurs and other prehistoric fauna sculpted by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, which are dotted about Crystal Palace Park in life-like settings: a powerful environment in which to grow a child who dreamed of wonders.

[How strange. I lived at Crystal Palace for most of the 1980s, and took part in a costume party where we pretended to be time-travellers hunting the plaster dinosaurs with ray-guns. During that time I bought an ex-library copy of The Apple-Stone from Anerley Library – with no idea that it must have been Gray’s own local library when he was a child.]

We know from Gray’s interview in The Pied Pipers that the family could afford a large house and a nanny. Nicholas/Phyllis began writing plays to amuse “my brothers and sister in the nursery” when s/he was “About ten. I wrote stories, and then I would dramatize them. We had a very big nursery with an archway at one end. My mother arranged a curtain for this, and we did plays behind it. She gave us kitchen paper and a screen or two, so we could paint our sets and pin them up. We used to knock up a play in an afternoon and do it in the evening. We charged people a penny admission, and there was no talking.”

Gray spoke often of his mother and never, that I’ve seen, of his father: but his father would have been thirty-four at the start of World War One, and as such was probably called up in June 1916, when conscription was extended to include married men between eighteen and forty-one. The Electoral Register describes him as a naval or military voter as at 1918. He would have been absent for some of Nick’s formative years, and possibly a bit withdrawn when he did return. And if Phyllis/Nick was already starting to feel like a boy, he might have felt it was up to him to be “the man of the house” already when he was four.

In any case his father seems to have spent a lot of time at his and his father’s (that is, Gray’s grandfather’s) business address in Southwark. It’s not entirely easy to trace the family because there seem to be two or three Arthur William Hatches in London around that time, complicated by the fact that the main source for the nineteen tens and twenties is the Electoral Register, and women over thirty didn’t get the vote until 1918 (Lenore was thirty-five) and so weren’t recorded, so I can’t get an entry and address for Lenore prior to 1918. In 1928 all women of twenty-one and over got the vote, in time for Phyllis who was still a teenager. But I managed to ascertain that in the 1911 census, just a few weeks before his marriage, Arthur was at 27 West Heath Drive, Hampstead, as stated on his marriage certificate, with his parents and his sister, and that the house was called St Servan (the name of a Breton port captured by British troops in 1758 during the Seven Years’ War). The birth certificate for Phyllis shows that s/he was born at 61 Silverdale, Sydenham (like Weighton Road, since built over with modern housing) in October 1912, and in 1913 and 1914 the Electoral Register likewise shows Arthur William Hatch at 61 Silverdale, Lower Sydenham, so we can assume Lenore and Phyllis were with him.

In 1915, however, Arthur William Loriot Hatch and Alfonse James Hatch are both voting from their business address at 200 Borough High Street. In the late 18th and early 19thC the building was the Red Cross Inn, Southwark, with strong masonic connections. In the early 20thC it was evidently business premises and tenements. By some time prior to 2008 up until at least spring 2018 it was the Café Riva and London City Hotel. By spring 2019 it was the City Hotel and City Café, and by late 2020 it was a 3-star hotel called CitySpace.

Usefully, the Electoral Register at that time listed people’s home addresses as a side note if that wasn’t where they were voting from, so we can see that Alphonse James still lived at St Servan in Hampstead in 1915, even though he voted from his office. Arthur William was now at 31 Sneath Avenue, Golders Green, with no information on whether Lenore and the children (at this point, just Phyllis and Arthur Maurice) were with him. However, remember that Arthur Maurice Hatch, the family’s second child, had been born in Hendon in March 1914, and Hendon is only about half a mile from Sneath Avenue, so he may well have been born in a hospital in Hendon while the family was based in Golders Green.

In 1918–1920 Alphonse and Arthur Sr are still voting from 200 Borough High Street, but Alphonse is now living at 31 Wentworth Road, Golders Green. Arthur is listed as NM (naval or military voter) in 1918, and as R (residence qualification) in 1919 and 1920 with no separate abode listed, suggesting he was now actually living at Borough High Street. This suggests he may have been absent from the family from 1916 at latest, when he would have been called up, until 1920. The whereabouts of Lenore at this point is unknown: their third child Winifred was born in Branksome, Dorset in February 1919, but we don’t know if Lenore was living there or just visiting.

In 1921 the census shows Arthur, Lenore and the by now three kids (with a fourth very much on the way) all living at 13A Weighton Road, Anerley. Phyllis was eight. They are still there in 1922 and 1923 although all of the adults, Alphonse, Arthur and Lenore, vote using 200 Borough High Street as their base. The fourth child, Robert Dudley, was born in Croydon in June 1921, but that was probably a hospital address as Croydon is a couple of miles from Anerley. The 1922 Electoral Register is a mess, incidentally, and calls the house 13A Wakeling Road, Anerley (there’s no such road) and Lenore “Leonine”.

In 1932, Arthur and Lenore are living and voting at 15 St Keyna Avenue, West Hove, on the west side of Brighton: Brighton being the town where Arthur had been born. From 1933–1935, by which point Phyllis was old enough to vote but had left home, they are still living at St Keyna Avenue but are back to voting from 200 Borough High Street. The location of the family as a whole during the years Phyllis was at secondary school, from autumn 1924 to the late 1920s, are unaccounted for (although there is some evidence of where Phyllis was, of which more anon), so either Arthur and Lenore didn’t vote in the 1924 and 1929 elections, or they were living somewhere whose Electoral Register is not yet available online.

The Hatch children’s early dramatic productions were, Gray said, “Mainly rather weird dramatizations of books I had just read. We would have a go at Walter Scott – why not? So my sister, aged six, would teeter about in a long skirt.” (when Winifred was six Nick/Phyllis would have been twelve or thirteen). In an interview in Plays and Players in January 1955 Gray said that he started writing plays for children even younger, before the birth of his sister in 1919, or at least before she was old enough to take part. He referred to this as having happened “about thirty years ago”, but in fact it was closer to forty years ago, and a review of The Marvellous Story of Puss in Boots in the Birmingham Weekly Post and Midland Pictorial on 9th December 1955 calls him “a young dramatist still in his early thirties”. So we know that by 1955 Gray was already shaving ten years off his age. At any rate, in the Plays and Players interview he says that:

As soon as I could speak, I am informed on impeccable authority, I made up dramatic scenarios in the nursery. These were taken so seriously that, the same maternal authority assures me, my eldest brother tore up a cuddly bear because it had suddenly been promoted to leading lady.

Later the addition of another brother and a sister made casting less difficult. When it was glaringly obvious that no other activity could keep me quiet, and my close kindred were quite cowed by my enthusiasm, the nursery was fitted with a stage at one end and real curtains, screens on which could be hung painted scenery of cupboard paper, and boxes of costumes and props . . . all home made.

The plays went on sometimes with one day’s rehearsal. We stopped at nothing. Books we had read, pantomimes we had seen, the imaginings of what I can only regard from this distance as a blood-thirsty mind, all were dramatised and performed . . . sometimes to the undisguised horror of the conscripted audience.

The blood-thirstiness of small children was a theme in some of Gray’s novels: in The Apple-Stone, for example, a couple who do a cutesy kids’ TV show with rabbit puppets start to wonder if the children would like them a bit more violent. He believed children were naturally savage, unless taught better. “I know I’m very gentle with animals, but when I was a very small boy I blew a frog up with a bicycle pump, and watched it swell. An older boy saved the frog and told me off. It never occurred to me I might be hurting it.”

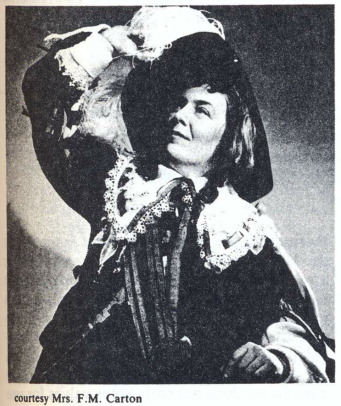

Later in the same Plays and Players interview Gray refers to “dreams of a real theatre for children—the dreams that started long ago, from my own point of view, with a small boy playing in the nursery, and insisting that Edward Bear was word-perfect, and must sit up straight.” Given Gray’s early love of the theatre it would be unrealistic to assume that he waited to break onto the professional stage until he had transitioned. Indeed, a trawl through the British newspaper archives shows numerous references to a Phyllis Hatch who was a teenager of the right age in the right sort of area and who was heavily involved in amateur drama and music; and an actress of the same name who enjoyed some success in London in the mid 1930s, and then disappeared as if by magic just before the first mentions of a Nicholas Stuart Gray.

We know that the Hatch family were living at 13A Weighton Road Anerley in 1923 when Gray was ten or eleven and his siblings were nine (Arthur Maurice), four (Winifred) and one or two (Robert Dudley). We know that by 1932, when s/he was nineteen, their parents, and presumably Winifred and Robert, were living at 15 St Keyna Avenue, West Hove. Without a definite date for the move it’s impossible to say at which address the nursery with the stage alcove was, but since Gray speaks of acting from a very early age, and doesn’t mention a house move prior to the construction of the stage, it was probably in Anerley, under the lee of the Crystal Palace.

Searching the newspapers archives shows lots of references in the Croydon Times (a South London paper) to an amateur actor and singer called Phyllis Hatch who was a pupil at the Progressive School of Music (described as “under the direction of Mrs. E. S. Tardrew, L.R.A.M. … her well-known school of music, elocution and dancing”) and a member of the school’s troupe, the Progressive Players, up until 1930, and then references to a Phyllis Hatch from Brighton in 1932. If it’s the same Phyllis Hatch s/he lived in South London at least until s/he was seventeen, although latterly s/he was based, or at least at school, at Addiscombe in Croydon, a couple of miles south of Anerley. I haven’t been able to find whether the rest of the Hatches were also in Croydon at this time, or still in Anerley, or already in Hove.

In May 1928 Phyllis came second in competitive elocution (in the category for ages 15 and 16, confirming s/he was the right age to be the right Phyllis) at the Croydon Musical Festival, with 88 marks. Later that month the Progressive School of Music put on a show at the Large Public Hall in Croydon, to raise funds for the school’s Scholarship Fund. The Junior School put on an “extravaganza” called Knave of Hearts, based on the nursery rhyme. Phyllis played the King of Clubs, described as an “exacting role”, well portrayed. By August the same year she was described as a Senior Student of the Progressive School, taking part in a half-hour concert at a gala in aid of the Addiscombe Wesleyan Church Young Men’s Institute and Rover’s Football Club.

In November 1928, when s/he was just sixteen, s/he played Bassanio in a Shakespearean medley as part of a prize-giving at Addiscombe School, presumably a regular secondary school and apparently (judging by the cast list) girls-only, with two headmistresses called Miss Dawson and Miss Martin. In January 1929 the Progressive Players put on an “outstanding number”, a playlet called Michael, written by Miles Malleson and adapted from Tolstoy’s What Men Live By. Phyllis played the title role and “well deserved the appeal [typo for applause?] that greeted her final speech”. In February 1929 the Progressive Players put on two evenings of repertory performances on behalf of the Croydon Voluntary Association for the Blind, and the Baths Hall Rendezvous Club, including another performance of Michael. Phyllis was in it but it doesn’t say in what role. Michael was produced by Miss Mary Challis, described elsewhere as an elocution and dramatic art instructress. In May Phyllis came first this time in competitive elocution (again for ages 15 and 16) at the Croydon Musical Festival, with 95 marks.

In March 1930 Phyllis successfully sang The Ballad of John Nicholson (a musical setting of a very dramatic but highly pro-colonialist and slightly racist poem by Sir Henry Newbolt) as part of a fundraiser for the Croydon Division of the St John’s Ambulance Brigade, put on by the Progressive Players in the North End Hall, and in May s/he took part in one or more of four “charming” fairy plays put on by Miss Challis’s pupils to raise money for the St Agnes Home for Cripples. In July 1930 s/he was selling tickets for a show called Scenes and Songs from Shakespeare’s Plays being put on by The First Tudor Players, and her address (at least for ticket-buying purposes) is given as 81 Stretton Road, Addiscombe, Croydon. In July 1931 The Stage reports s/he took part in an elocution contest held by the British Empire Shakespeare Society (BESS), where competitors read from the works of Shakespeare. The report doesn’t say how well she did or where she was living. When we say “elocution” nowadays I think of Pygmalion and people suppressing their natural accents in favour of a plummy uniformity: but these BESS events were more like mass auditions, with hopeful thespians competing to give the best reading of a piece from Shakespeare.

In May1932 at the Brighton Music Festival, P. Hatch, B. Bevis, J. Avery, J. M. Griffiths, and G. Powis, appeared in a play by Phyllis Hatch who is said to live at Haywards Heath, a small town fourteen miles north of Brighton, and may or may not have won the Challenge Cup for modern one-act plays: the Mid Sussex Times of 24th May 1932 says Phyllis’s play came second, but the West Sussex Gazette of 2nd June 1932 says it was a tie. A couple of months later Phyllis Hatch of Brighton was highly commended in the annual BESS elocution contest (The Era 20th July 1932). It has to be the same Phyllis Hatch because of their previous appearances in elocution contests, and the fact that there is no more mention of Phyllis Hatch in Croydon. Also, by living at Haywards Heath Phyllis was showing the same pattern which was to follow Nick all his life: living near his family but usually not with them. In July 1933 Phyllis was one of nine competitors for the “coveted Ellen Terry Cup” at the annual BESS elocution contest, but didn’t win. By November 1933 s/he was at Sadler’s Wells and the Old Vic, assuming this is the right Phyllis (and by 1938 or ’39 s/he was a he).

According to his Pied Pipers interview, and despite his childhood love of writing his own plays, Gray’s great preference was for Shakespeare. As soon as he was old enough, he said, he joined a local dramatic society who put on scenes from Shakespeare – which pretty-well proves he was the ticket-touting Phyllis in Croydon in 1930. At the time of the interview in 1973, Nick was especially pleased to have recently played Iago. I know he played Iago once, at the Malvern Theatre in 1966. Elsewhere in the interview he refers to an incident with his mother, who died in Northam, Devon on 28th May 1965, as having happened a couple of years ago, yet the interview is marked 1973, which suggests that at sixty, as he then was, his sense of time was a bit faulty: possibly he had played so fast and loose with his own timeline that he was no longer sure when anything happened. [His obituary in the Annual Obituary 1981 compendium, edited by Janet Podell, pub. Thomson Gale, says he played Iago at the Malvern in 1969, and if indeed he played the same part twice, at the same theatre, he may have got confused as to which performance of Iago had happened soon after the meeting with his mother – but I can find no other evidence of a performance of Othello at the Malvern in 1969, so I think that the obituary writer, too, is confused about Nick’s timeline.]

In the Pied Piper interview, he said of Iago that “It’s no good playing Iago as a moustache-wiggling villain, because it makes idiots of the rest of the cast. You’ve got to have the audience saying to itself that it believes hm. He should be charming to them all, and terribly worried, until the moment when everybody goes off stage and he’s left alone.” This perhaps explains the mixed and even contradictory reviews for his 1966 Iago at the Malvern, described by one reviewer as being played “with drive and force as a smiling villain with no marked subtleties”, and by another as a “curious Iago, who lacks the obsessional ruthlesness of the worst villain of them all”.

According to Annual Obituary 1981 Gray was an atheist (not surprising in the UK, even then, but it sits a little strangely with the tenor of some of his stories, so it may just mean “Not a member of an organised religion”). The person who composed the obituary either wasn’t paying attention, or couldn’t count. They repeat happily that Gray was born in 1922, then say he was “Active as stagehand, actor, director, playwright throughout England 1933—75”, without thinking about the fact that that would mean he started work when he was ten or eleven, without any other suggestion that he had been a professional child-actor, and that “In 1938 he was the director and organizer of the Try-Out Guild, a group formed to test the interest of management in new plays”, without asking how likely that was if he had indeed been fifteen or sixteen at the time. That in itself should have told everyone that Gray was born well before 1922.

Gray (as Phyllis) attended “various private grammar schools” in England, but never went to college or got a degree: he said of himself that “I never tried any, and probably wouldn’t have got them if I had done so”. The fact that he went to “various” grammar schools is suggestive: unless their families move around a lot most people only go to one, but in those days nearly all grammar schools would have been single-sex, and “Phyllis” probably didn’t fit in very well at an all-girls’ school. It was, at least, the Roaring Twenties, an era when it was acceptable for girls to be loud, extrovert and a bit androgynous; and it was probably also still acceptable for girls. even in Gray’s age-range, to be without a boyfriend, since in the age-range twelve to thirty-five years ahead of him so many young men had died in the trenches.

On the other hand, s/he must have started at secondary school in autumn 1924, and in November 1928 (when s/he had just turned sixteen) s/he was at Addiscome School in Croydon (whether or not the family were also in Croydon or already in Hove). If the move to Croydon was after 1924 that would account for at least one change of grammar school, from one in or near Anerley to one in Croydon. Against that all reports including his own say he left school (and what was evidently a toxic relationship with his mother, of which more anon) at fourteen or fifteen to go on the stage, meaning he was only at grammar school for at most four years, and “various” sounds like at least three schools. Annual Obituary 1981 says “From the age of 14, Gray worked in the theater. At 16, he was an assistant stage manager for shows in London.” But we know s/he was still at Addiscombe School for a prize-giving a few weeks after their sixteenth birthday – so did he really go on stage in his teens, or was that another bit of temporal sleight of hand?

As already mentioned, a Phyllis Hatch, presumably Phyllis Loriot Hatch the Shakespeare lover, was a fairly successful actress in London in the 1930s, appearing in numerous medium-level roles in “serious” theatre, including at the Old Vic, and also did some stage-managing, before completely disappearing after the mid 1930s, to be replaced by Nicholas Stuart Gray, playwright, of whom there is no sign before 1938 at earliest. It seems clear that the reason he shaved ten years off his life and claimed to have been born in 1922 was so as not to have to explain what happened during the ten or so years when he was performing successfully under what was to become his dead name. And while saying he left school at only fourteen or fifteen to go on the stage is clearly being economical with the truth, it’s not that big a whacker (to use his own phrase). S/he did apparently attend a stage school (the Progressive School of Music) at the same time as regular school, since s/he was describes as a Senior Student of the Progressive School of Music in August 1928, months before the Addiscombe School prize-giving where s/he played Bassanio. And if Phyllis Hatch, actress is indeed Phyllis Loriot Hatch, as she certainly seems to be, well, s/he was a member of the Old Vic Company at twenty-one, so while Phyllis/Nick may not have exactly left school to go on the stage professionally at fifteen, s/he had certainly done enough amateur performances and won enough prizes in their late teens to make a name for themselves.

In November 1936, the Crystal Palace burned: and even though the Hatch family was no longer living near it, that must have been a disturbing event for anyone who had grown up under its glittering gaze. The Electoral Register shows that in 1938 and 1939 Phyllis Loriot Hatch was living with their mother Lenore May Hatch and brother Arthur Maurice Hatch at 143 Dartmouth Road, Mapesbury (along with five other people, so it was probably some kind of lodging house or block of flats). In 1938 Arthur William Hatch, the father, was with them, but by 1939 he had apparently moved. Given that “Nick” first appears in the theatrical world (or indeed anywhere) under that name in 1938 (as director of the Try-Out Guild, according to Annual Obituary 1981), he was evidently staying with his parents when he transitioned, socially if not yet medically. It could be that his father’s non-presence in the family home in 1939, and the fact that he never seemed to mention his father, was because his father was unable to accept the transition from daughter to son.

On the other hand, there’s no actual date on the Electoral Register, other than 1939. If it was after the start of WW2, or after it was clear that WW2 was imminent, it could be that even though he was nearly sixty, Arthur Hatch Sr had gone away to do something connected with the war effort. Since he was an inventor and a businessman, and probably fluent in French, it might even have been something Gray still wasn’t allowed to talk about in the 1970s.

I can find no record of Phyllis Hatch as an actress after 1935, although s/he was still registered to vote under that name until 1939. According to his obituary s/he was working as Nick in 1938, as leader of the Try-Out Guild, and he was certainly being named as Nicholas Stuart Gray in the press by April 1940. It looks as though he must have taken a couple of years out from acting so that when he returned as Nick, people wouldn’t immediately recognise him as Phyllis whom they had seen perform a few weeks ago.

I must say that my first thought, on realising that Nicholas Stuart Gray and Phyllis Loriot Hatch were the same person, was to bury the information, because Nicholas himself had concealed it. But such a prolific actor and author would surely not want to be forgotten. When she was eighteen Cassandra Golds wrote him a fan letter, and he wrote back saying “As all my books and plays are only written for myself and not for any imagined audiences, readers, age-groups, publishers, etc, it is always a delightful surprise to get proof that anyone BUT myself ever reads or sees them”, so he would certainly be very pleased that people were still interested in his work more than forty years after his death. And if Gray is publicly remembered, sooner or later somebody else who understands genealogy research is going to realise there’s no record of his birth in Scotland, send off for his death certificate and see: “Cause of death … c) Ca Ovary (*NB Sex Change 1959)”. And, OK, I’m especially good at ferretting out information because I used to actually work as an Information Analyst, but still, given that the 1921 census is now available it only took me half a day to get from the death certificate to Phyllis Loriot Hatch, so sooner or later the secret will out.

Also, Nick presumably hid his secret from the world at large (although there must have been people in the acting world who knew) for fear that people would look askance at him. But he’s been dead for forty-two years, and these days people are more likely to find the fact that he was one of the first people in the world to have an official F2M sex-change interesting rather than shocking. And as an actor, he might like finally to be recognised for the role he pulled off every day of his life: first as a girl and a successful actress when he evidently didn’t feel like one inside, and then as a man and a successful actor when he hadn’t grown up as one and didn’t have the full kit of parts. He lived as a man for twenty-one years before he even had the official sex-change, without anyone outside his family and immediate circle knowing, and that deserves a standing ovation and three curtain calls.

Initially, I also wasn’t sure what to do with the information that the writer who had shaped much of my understanding of human gender roles had not grown up as male in the usual sense, and hadn’t really grown up as female either. But, after all, like Polly Perks, the heroine of Terry Pratchett’s Monstrous Regiment who must live as a male soldier in order to find her missing brother, Gray must have made a study of what it meant to be male, and how to be accepted by others as male, much more intense and analytical than that of most cis men. [Pratchett’s/Polly’s summary of the average teenage boy: “I’m rough, I’m tough, I’m mean; mine’s half a shandy and me mum wants me home by nine.”] Although it probably helped that he had chosen a profession where men being a little bit feminine was par for the course.

He must have felt very strongly about his need to transition to male, when that meant throwing away an already-promising career and starting over, in a field where being female was no barrier to success, on the brink of a World War which many felt was coming, and in which being male could get you killed. To me this is always slightly baffling because I just feel like a me: I’m happy enough to be a woman, but if I woke up tomorrow as a man then aside from the initial “Well, how the Hell did that happen?” and adjusting to the change in reach, I don’t think it would bother me at all. But Gray’s dysphoria must have been overwhelming.

Gray’s reason for identifying his new male persona as Scottish was probably to explain how come he was suddenly director of the Try-Out Guild in London with no apparent theatrical history: rather than saying “You know me better as Phyllis Hatch”, he must have said he’d been acting in rep. in Scotland for ten years. Those in the theatre who knew who he was kept quiet about it, and for everyone else, in the days before internet newspaper archives it would have been very hard for anyone from London to check. Later, when he became well-known as Nicholas, he clipped those ten years out of his life to stop people in Scottish theatre saying “Never heard of ‘im”. Meanwhile, claiming to be Scottish and giving his mother his Scottish grandmother’s maiden name enabled him to keep some contact with his real family history. He must have been quite lonely: outside of his immediate family and friends he couldn’t know anyone he’d known growing up. Unless he was willing to switch back and forth between male and female personae, which would have been terribly risky, there could be no school reunions for him; no “You were our newsagent when I was seven”, no “You were my dresser when I played the Old Vic”.

Another reason for shaving ten years off his age may have been because at the beginning of World War Two, when Gray was living in Sussex and already identifying as male, he wanted to do his bit. If he’d still identified as twenty-seven-year-old Phyllis he wouldn’t have been allowed in the Home Guard: he could have joined one of the women’s services, but then he’d have been stuck still living as a woman, which he evidently disliked doing, for however long the war would last. If he’d admitted to being twenty-seven while living as a male he would have been called up into the forces, with dire consequences the first time s/he had to undress in front of other soldiers. By presenting himself as a seventeen-year-old boy he was able to join the local Home Guard, as well as being able to pass off any perceived girliness in his bone structure as being due to youth. How he avoided being called up later in the war is an open question: I suppose he had a quiet word with an army medic about his still-official feminine gender, and they didn’t rat him out.

In his interview in The Pied Pipers he says that during “the hostilities”:

I ASMed (Assistant Stage Managed) various shows in London. I was also a member of the Home Guard in Sussex. I exploded hand grenades. [Intentionally?] Well, no, not always entirely. Our country laddies down there were very worried by the ranking regular army gentlemen who would come on the scene from time to time. I used to say to them: “Don’t worry, you’re all snipers, and that’s really all; and if there is an invasion, then all we do is climb trees heavily disguised in leaves and try to pick off two people before they shoot us. So take no notice of them. Just laugh.” They used to come, the military gentlemen, and ask: “Where is everybody?” And you’d say: “Well now, there’s our Fred, ‘e’s gathering the hay this afternoon.” These young men would come up to me and say: “Nick, I’ve taken the pin out. What do I do now?” I’d say “You throw it over there as far as you possibly can and run, lovely.”

Questions have been raised as to whether he really could have been in the Home Guard, and whether he borrowed the history of one of his brothers, but I don’t see why he wouldn’t have been in the Home Guard: he was evidently already living as a man, since the press referred to him as Nicholas Stuart Gray in April 1940, and I don’t think there was any requirement for Home Guards to strip, since they weren’t living in barracks. Family information is that Arthur Maurice was in the Home Guard, but in Hendon not Sussex: he wasn’t called up to actual military service because he had lost half the sight of one eye in a childhood accident. Robert Dudley served, possibly in the Middle East, and then was invalided home: it’s not known whether he too was in the Home Guard or not.

Even if Nick was in the Home Guard, though, he must have run into trouble before long, because even with having shaved ten years off his age, by late October 1940 he was officially an 18-year-old boy and would have been expected to do military training. Annual Obituary 1981 says that he worked on the land during the war: this made me wonder whether maybe the army medic did rat him out, and he ended up as a Land Girl, but family memory is that he signed up as a Conscientious Objector, which I’m told would have allowed him to work the land in his male persona. This cannot be absolutely confirmed because the records for the Conscientious Objectors were destroyed, but his doctors have to have been aware that he was anatomically female, and probably helped him to get CO status without too many questions being asked

It was during this period, in 1944, that Gray’s father died, less than a year after his father Alphonse.

None of Gray’s fellow actors seem ever to have betrayed his secret, although many must have known: but then as now many actors must have been gay, in an era when being gay was still illegal, so actors were used to keeping quiet about each other’s private lives. Covering up for a fellow thespian who was transsexual was probably just more of the same.

Gray’s first professionally produced play is claimed to have been performed in London when he was seventeen – when he was really seventeen, or only claiming to have been? Asked what was his first professional acting experience, he said “Oh God – it must have been at Windsor, where I also did a production. And then I wrote a play and put that on … a whodunnit for adults, called Judgment Reserved. Then at the end of the War I had another play done, called The Haunted, at the Torch Theatre in Knightsbridge (London), and then on television.” A search of the newspaper archives shows Judgment Reserved was performed at the New Lindsey Theatre in London in April 1940, which is mildly disappointing, since having a play produced at twenty-seven is less impressive than having it produced at seventeen. [The frequent references in 1950s reviews of his plays to the renown he was then achieving at such a comparatively young age also fall a little flat when you know he was ten years older than the reviewers thought.]

References to Judgment Reserved in 1940 represent the very first mention I could find in the press of the name Nicholas Stuart Gray. By 1948 he was already fairly well thought-of under his male persona, because The Haunted was chosen to premiere as the first play performed at the new Torch Theatre, Knightsbridge in August 1948, and was so liked that it was picked up to be broadcast on BBC radio in October of the same year.

Gray got the idea of writing plays specifically for children in 1947/48 after seeing that there were radio and TV shows for them, and children’s cartoon matinées in the cinema, but nothing in live theatre except pantomime, which most children were bored by. He didn’t even especially like children, he said, but he wanted to introduce children to live theatre young in order to ensure an ongoing audience when they grew up, because live theatre has an electricity between audience and cast which you don’t get with pre-recorded mediums, and which is worth preserving. In his Plays and Players interview he spoke of “an adopted nephew of mine” who was nine at the time (so born in the late 1930s) and who hated pantomime because “there was no story, and too much slop”.

A few years later, on 22nd December 1955. the Derby Evening Telegraph would say that Gray “believes that pantomime has a nostalgic appeal for grown-ups for whom it recalls their own youth, but has little to offer the modern child. // He feels that the three main ingredients of pantomime will be split up—the spectacular side going on to new strength in ice pantomime, the variety side reverting to the variety stage and the fairy-story themes forming the basis of a ‘straight’ children’s Christmas theatre.” He wasn’t far wrong. although the spectacular “on ice” performances of the 1970s eventually gave way to flamboyant musicals; the racy aspect of pantomime split off into drag shows of the late night variety; variety itself was largely relegated to Red Nose Day and the Royal Variety Performance; and children’s theatre is now mainly on film rather than live, while retaining the tendency which Gray started, of re-telling traditional fairy stories with modern wit and lively dialogue.

The adopted nephew who thought pantomime was slop is mentioned nowhere else, and is not one of the people to whom Gray left copyrights and royalties. There’s no knowing whether the boy had died, or become estranged from Gray, or was simply too wealthy and successful to need to have anything left to him. Nor do we know whether he was someone Gray himself had unofficially adopted as a sort-of nephew, or someone who had been formally adopted by one of Gray’s siblings. At least, his existence explains why Gray’s first children’s play to be performed, Beauty and the Beast, revolves not only around the title characters but also around a fussy, absent-minded middle-aged wizard cum gardener and his adopted nephew Mikey, a baby dragon. [The Tinder Box was actually written first, in 1948 (which explains its rather clunky intro. and first act), but not performed until Beauty and the Beast had started to make Gray’s name.]

Beauty and the Beast was written (or at least completed) in 1949, with Nick Gray and Joan Jefferson Farjeon working together on the overall design. It was first performed at the Mercury Theatre in London for five weeks over the Christmas season of 1949/1950. Two days after his death, on 19th March 1981, The Daily Telegraph described this event thus:

If anyone shouted “Eureka!” on first spotting the talent which made Nicholas Stuart Gray the most important and uncondescending of dramatists for at least two generations of children, it was Kitty Black, the translator and adaptor, who was working at the Lyric, Hammersmith, one Saturday morning in the late ’40s when as unsolicited script called “Beauty and the Beast” thumped on to her desk.

“I had nothing better to do”, she recalled yesterday, “so I started to read it, went straight through to the end without putting it down, then telephoned him and arranged to meet for tea at 4 p.m.” Thanks largely to pressure from Miss Black, the play was staged at the Mercury at Christmas, 1949, when it broke the house record by taking three shillings and sixpence, less fivepence tax, leaving total receipts of three shillings and one penny. But a glowing review by Beverley Baxter [who called it “a perfect miniature”] produced a week of sell-outs and the start of a world-wide success for Gray and his inseperable designer Joan Jefferson Farjeon.

In 1952 The Telegraph said of the play that “Its simplicity has an extraordinary quality. Though the story is told almost in words of one syllable, it gives you a feeling as though you were looking down into deep, clear water.” As a result of the play’s initial success Gray, Joan Jefferson Farjeon and Kitty Black founded the London Children’s Theatre company. In 1961 Beast was performed on BBC TV as that year’s Christmas play for children.

Back in early 1950, though, Gray was, he said, “almost paralysed . . . with astonishment” at the play’s immediate success, and as a result he was now well-known enough to be picked to read a 15-minute play of his own called Gunpowder Guy on TV on 5th November 1950, summarising the story of Guy Fawkes for children (and considered good enough to be put on again in 1953). The Tinder Box premiered in Liverpool seven weeks later. In 1951 Beauty and the Beast was mass-printed and published. The Princess and the Swineherd followed in late 1951 with a production at Toynbee Hall, funded by the LCC (London City Council), and was shown on the BBC that Christmas; and in May 1952 an unpublished children’s play by Gray called Leading Question, about the famous “And when did you last see your father?” painting, was also produced on TV.

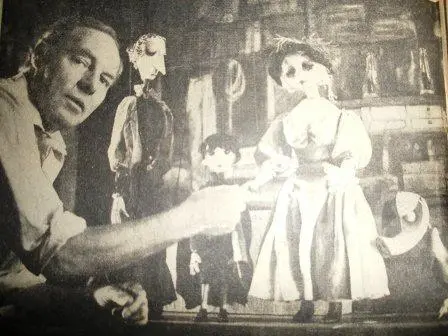

In 1953 came the first version of the play variously known as Rapunzel, The Golden Plait, The Wrong Side of the Moon and The Stone Cage, and in the US as The Stone Tower. This first draught was written to be performed by John Wright’s Marionettes during a Christmas season of puppet-plays at the Mercury Theatre in 1953. Gray had done some voice-acting for them the previous year for a play called Hans the Bellringer. He continued throughout his career to do straightforward acting gigs, as well as acting in and directing his own plays, which were added to every year or two: by 1956 The Birmingham Mail was referring to him as “the usual Christmas author”. Meanwhile the London Children’s Theatre company tried unsuccessfully to get up enough government or philanthropical funding to establish a permanent venue dedicated to putting on children’s plays (interview with Kitty Black, The Stage, 29th December 1956). Gray’s plays continued to be generally very well received for their combination of story-telling and wit, although there were occasional complaints that they moved too slowly, or that too much time had to be devoted to scene changes. His plays were showcased every year at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, which had a revolving stage which enabled different scenes to be rotated into view at will, and I guess he got too used to the ease and speed of that.

I can’t help thinking how very well Gray’s plays would work on film in CGI or stop-go animation, or live action plus CGI for the creatures – or indeed as graphic novels. That would solve the scene-changing problem, and also get rid of much of the need for clunky exposition: characters wouldn’t need to talk loudly about a white mouse eating a crust of bread if you could actually see the thing and zoom in on it. Given that Gray wrote his plays specifically to get children interested in live theatre, transferring them to film might seem like a betrayal: but it would get his stories out there to a new generation, and The Cursed Child and The Lion King have shown that children are more inclined to go to live theatre, and ooh and aah over mechanical special effects, if it’s based on a story they’ve already grown to love on the screen. And after all, The Stone Cage was originally written for puppets, and animation is just a puppet show in which the puppets are made of plasticine or code or pen-and-ink drawings, rather than wood and strings.

Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature Vol 2 by R Reginald, Douglas Menville and Mary A. Burgess says that Gray’s roles outside his own plays included Hamlet, Richard II and Iago, that he was a member of P.E.N. and the Société des Auteurs, and that his agent was Samuel French Inc, 25 W. 45th St, New York, NY 10036. In his plays, his UK agent is given as English Theatre Guild Ltd, 5A South Side, Clapham Common, London SW4 9DH. US performing rights for The Stone Cage (under the much less resonant name The Stone Tower) were granted exclusively to the Equity Library Theatre for Children. He went on to write twelve published plays for children (although Beauty and the Beast remained the most popular); at least two unpublished plays for adults and two (plus one “scientific entertainment”) for children; eight novels, one novella and three collections of short stories for children; one adult whodunnit novel; one collection of poetry and one book of autobiography centred on his cats.

There’s also a strange attribution in The Sydney Morning Herald of 18th March 1960, which may be an error. It advertises that the Independent Theatre in North Sydney will be putting on the play Mr Pompous and the Pussycat by Nicholas Stuart Gray. This play is actually by the actress, playwright and suffragette Cicely Hamilton. I don’t know whether the Independent Theatre, which frequently performed Gray’s plays, had absent-mindedly attributed it to him because it included a witch and a talking cat and the theatre staff automatically assumed that all such plays belonged to the master; or whether Gray had genuinely done some work on updating the script. I have seen at least one website including it among Gray’s plays, but I suspect they were misled by the Australian notice.

In an interview in The Stage on 18th November 1954, Gray spoke of his hope that famous playwrights such as Terence Rattigan might get into writing plays for children, and said:

A point that many people do not realise is that there is no question of having to write down for children. You have to write for children in just the same way as for adults—only better ! Young people are much more critical than the general audience : they never stop asking how ? and why ? There must be logic in everything you write for them. When I made the magician in “Beauty and the Beast” place a mark on a tree trunk, saying that the mark would be seen higher up as the tree grew, I was immediately criticised by a boy of seven, who pointed out to me that such a mark would grow out, not up.

… sincerely played … plays become completely real to youngsters, who enter into the story wholeheartedly. When justice ultimately overtook the villain in a performance of one of my plays an angelic-looking child horrified the lady sitting next to him by calling out : ” And serve you damned well right! ” …

The only wholly satisfactory way of writing these plays is to place every situation and piece of dialogue on two levels, so that neither the children nor the adults are ever bored at the expense of the other …

I want now, in my own case, to turn from adaptations of familiar fairy-tales … I am afraid of becoming too repetitious, so I am planning to write some straightforward adventure plays that might prove suitable during the Easter and summer holidays.

It was presumably this which urged him to write Leading Question and, previously, Gunpowder Guy, which seem to have been purely historical dramas, and also Gawain and the Green Knight which, while having a strong element of fantasy and magic, is not based on what one would normally think of as a fairy tale.

On 3rd January 1957, Winefride Jackson of The Daily Telegraph wrote:

Man on the way to making a small fortune is the author of this children’s play [The Marvellous Story of Puss in Boots, about to be put on at the Lyric, Hammersmith for a charity performance in front of Princess Alexandra], Nicholas Stuart Gray. His recipe for fortune: take a traditional fairy story, modernise the dialogue and some of the situations, be very sincere and make your magic logical. Mr. Gray has written six of these plays, they are all being played in various parts of the country now and have been translated into half a dozen languages.

I asked Mr. Gray how he assessed the appeal of his plays to children. “I write what pleases me. As I consider I have the IQ of an average child it seems to work.”

When I murmured that he was surely under-rating himself he replied, “Certainly not. The average child is very intelligent. One assumes that children grow cleverer as they grow older. Personally I think they grow more stupid. Young children have a merciless logic and are extremely critical.”

His relationship with his siblings, his original, childhood audience and cast, seems to have remained warm, since the family generally continued to live near each other, his sister Winifred illustrated two of his books, and he left his royalties and copyright to his three siblings and to his niece Anderida Hatch. His relationship with his parents, or at least with his mother, was less happy. In the Pied Pipers interview in 1973 he said that one of his intentions, in writing his plays, was to create something which could be enjoyed by parents alongside their children, not in a knowing, wink-wink pantomime way but by telling a story which was clever and amusing while being accessible to anyone of six and up, instead of splitting families into sharply-defined age bands. He and his siblings, he said, had been “left more or less on our own in the nursery. We would have been glad of adult company. If our dreaded Mum, instead of swishing about being Morgan le Fay, had been more with us, and not left us to our ancient nanny, I think we would have enjoyed ourselves a little more.”

I have to say that given the way he describes her, I’m not convinced they would have, and that indifference was probably the best they could hope for from her. She was, in his opinion, rather a tragic figure – someone who had been so dazzlingly beautiful as a teenager that she had never bothered to learn any mental skills except being decorative, and couldn’t cope with the fact that her beauty, although still considerable, was no longer that of a sixteen-year-old. “I’ve seen her staring into her looking-glass saying, ‘What have they done to you?'” Yet, she can’t have been as purely decorative and as lacking in skills as Gray paints her, since at the time of her marriage she was a hospital nurse: perhaps she regarded having worked for a living as infra dig, and didn’t tell him about it.

He had previously described her as “beautiful and terrifying”. In this interview he said that she was “… a megalomaniac … once we stopped saying ‘Yes Mummy’ and started saying ‘No Mummy,’ we were instant enemies. We were challenging her—especially me. The rest of my family was a little more peaceable. She spent the whole of her time trying to cut us down.” Whenever anyone complimented one of her children she would tell them the compliment wasn’t sincere and the person was just trying to get something out of them. “So we grew up terribly unsure of ourselves and doubtful of other people, always prepared to be cut down.”

He said that as recently as “a year or two ago” (which can’t be right if the interview was given in 1973, as his mother died on 28th May 1965) he had taken his mother to see one of his plays. Whatever else she may have been, it sounds as though she at least wasn’t freaked out by the Phyllis/Nicholas transformation: possibly she saw it as not so much gaining a son as losing a rival. “She said. ‘You wrote that play?’ ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘And you directed it?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘And you acted in it?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Who helped you?’ We were always ugly, stupid, gullible, useless people in her eyes.”

This casts an even sadder light on one of Gray’s most famous works and one of his few ventures into pure SF, the short story The Star Beast, in which a furry, vaguely monkey-like alien of indeterminate gender crash-lands on Earth and then is unable to convince humans of its intelligence, and ends up so miserable and discouraged that it tries to become the mere beast its captors assume it to be. He said that Mother Gothel, the witch in The Stone Cage, a.k.a. The Wrong Side of the Moon, was “almost a biography” of his mother, which is a strong statement given that the notes for the stage version describe Gothel thus: “A creature of malice, egotism, and cruelty. She is so interested in herself, that she has little time to spare for anyone else’s feelings or well-being. She considers the world against her, and beneath her. She is absolutely alone, and does not even realize that she minds the fact. … Once, long ago, she was beautiful. Now she would be avoided by anyone with sense.”

She’s also very free with slapping the face of anyone who disagrees with her in the slightest, as Nick said he himself had often disagreed with his mother as a child, or just because she’s tense and taking it out on her slaves. She wants to be loved, but doesn’t know how to be loveable, and veers alarmingly between overdone, sugary sweetness and demanding that her creatures should cower before her. It’s probably not coincidence that Rapunzel’s stone cage resembles the massive, lighthouse-like Crystal Palace water tower which loomed over much of Nick’s childhood, and that Mother Gothel’s slave-familiar Tomlyn, who cheeks her and gets hit and doesn’t care, and whose role Nick frequently played, is very specifically and emphatically described as a grey cat.

Likening his mother to Morgan le Fay is also significant. Morgan le Fay is another name for Morgan-Morgawse, the half-sister of King Arthur. In his superb version of Gawain and the Green Knight, Gray describes Morgan’s son Gawain as someone with whom he had “a feeling of oneness” and: “GAWAIN’S main difficulty in life is his endless war with himself. He can only relax when faced with something simple—like a three-headed dragon … His terrible mother has so sapped his confidence that he is always vulnerable. Too proud to endure criticism, and too unaccustomed to praise to believe it. He does not like himself, and is unwilling to risk liking others. He thinks no one else could like him, and thinks he does not care. His theories about life frequently trip him into falling flat on his face. He is about to embark on a hopeless battle not to fall deeply in love with his uncle, his aunt, and anyone else who throws him a kind word.”

Nevertheless, Gawain is portrayed as a bit of a daft lad (in several senses of the word “lad”), and Gray was in a fairly daft mood when he wrote it. Arthur and Guinevere are referred to as Bruno and Vera, and the introduction includes “PERIOD An intermingling of A.D. 500 and A.D. 1200. Malory did it, too, so see if I care.” The book also provides evidence that Gray spoke at least some Gaelic.

His relationship with his mother was clearly very complicated, for Nick dedicated Beauty and the Beast, his first children’s play to be staged, “To my mother Lenore, with love”, yet he both wrote and published The Stone Cage while she was alive. Either he was confident she would neither watch nor read it, or he was confident she wouldn’t recognise herself in it, or he was being a bit passive-aggressive and hoping to start a conversation without having to do it face to face.

From the sound of it Lenore also bore some resemblance to the beautiful but toxic and self-pitying Lady Ellen in The Other Cinderella. In fact, both The Other Cinderella and The Princess and the Swineherd revolve around spiteful, unstable, self-pitying girls who lost their mothers very young, as Lenore lost hers, and have been over-indulged as a result. In Gray’s stories kindness and true love are enough to stabilise them, as he hoped for his mother to stabilise: but in reality such histrionic and/or narcissistic types rarely improve without a lot of therapy, and the people who marry them are letting themselves in for a rough ride.

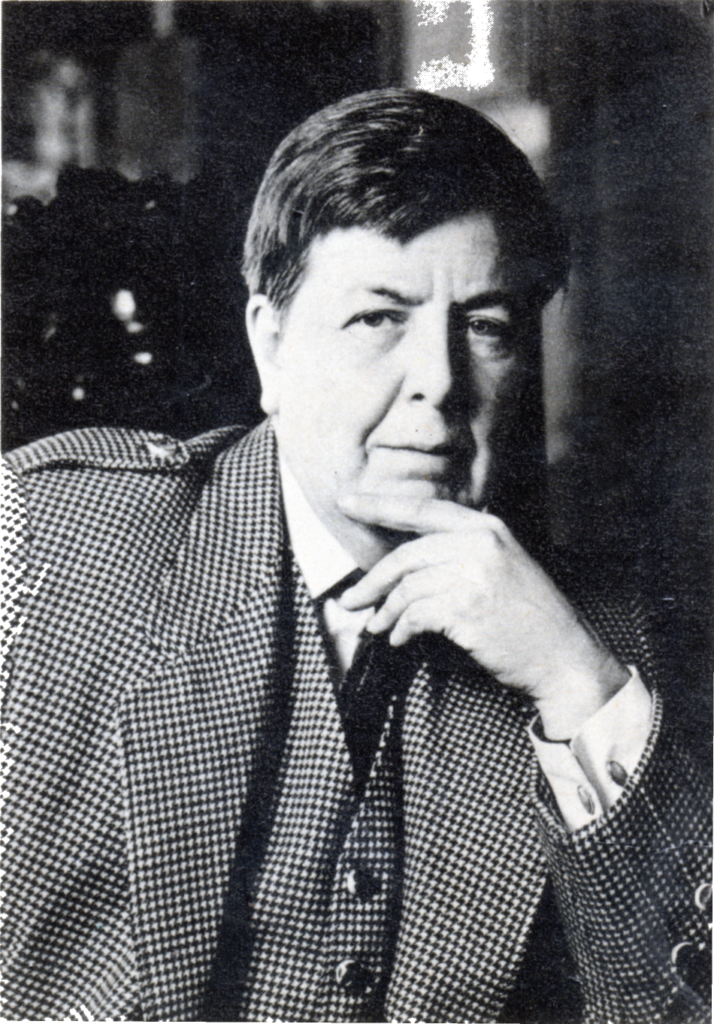

Still, he pitied his mother nearly as much as she pitied herself: “The sad thing about people like that is they are completely alone”. Gray too was very good-looking in an aristocratic, John Le Mesurier-type way, at least in profile, although he had, understandably, a rather soft jawline, and in later life he ran to fat (perhaps not unconnected with the fact that he was said to be a very good cook, and was friends with TV chefs Fanny and Johnnie Cradock). His Annual Obituary 1981 entry includes a photo’ of him on stage, which must have been taken not long after he began living as Nick as he looks about thirty, and decidedly androgynous. It’s pretty clear that when he was living as Phyllis he made the sort of good-looking woman one would call handsome rather than pretty.

Throughout his career Gray collaborated closely with his friend the set designer, costume designer and illustrator Joan Jefferson Farjeon. Joan, just seven months younger than Nick, came from a famous Anglo-American theatrical and literary family and was the niece of Eleanor, Herbert and Harry Farjeon, the daughter of the mystery writer Joseph Jefferson Farjeon, the first cousin of the stage director Gervase Laurence Farjeon and a descendant of Thomas Jefferson, but she must have been even more averse to publicity than Nick was: the internet is full of pictures of her art and her set-designs, but not a single one of her herself. She supplied scene and costume designs for many productions of Gray’s plays, and illustrations for most of his published plays and one of his novels. In this, he was in illustrious company, as Farjeon also did a lot of work with Agatha Christie, and was manager and amanuensis for the Cradocks. Gray and Farjeon were clearly very good friends, as they went on cycling holidays to Provence together.

A review in the Coventry Standard in August 1968 said that Gay also often designed his own sets, and sometimes even painted his own scenery. Among his many other skills, Gray was also something of a stage-magician when it came to magic-appearing props. Most of his books were published by Dennis Dobson, and Dobson’s son James describes him thus:

My father, Dennis Dobson, published almost all the books and plays and I often met Nick when he came into the office, which was on the ground floor of our house. He was a really lovely man – kind, gentle and humorous, and great fun watching him act in his plays. I particularly remember him as Puss, in Puss in Boots, and going backstage to meet him in full costume and make-up. In another play he had a magic tankard that would automatically refill on stage. We couldn’t imagine how he did it until he showed us the trick afterwards.